The presence of Jews in Barcelona has been documented since the existence of the Jewish quarter in the city, though it is not known whether they already formed a community. In around

850, tradition has it that there is a letter from the gaon Amram de Sura (Babylon) to the Jews of Barcelona. In 877 the Jew Judacot served as

an emissary between Charles II, the Bald, of France, and the people of Barcelona and

the handing over to the bishop Frodoí of ten pounds of silver to repair their church.

During Almanzor's attack on Barcelona (985) several Jews died and the properties of

those who had no heirs passed into the hands of the count.

The Usatges of Barcelona (1053-1071) include some provisions relating to the Jews. The first

documentary evidence of a Jewish quarter in Barcelona dates back to the 11th century when a street is mentioned que solebat ire ad callem judaicum. The word call means «little road» or «alley». The names spread to the whole set of streets occupied

by the Jews, in other words, the Jewish quarter, and the community of Jews received the name of Moorish quarter. The municipal authorities

had no jurisdiction over the Call which was directly answerable to the king or the royal bailiffs, but as from the

14th century restrictive ordinances for the Jews were issued referring solely to situations

or actions outside the Call quarter.

As in the rest of the Spanish communities, the Jews of Barcelona passed through different

stages of cohabitation with the rest of the city dwellers. Whilst in the 11th century

the famous Jewish writer and traveller Benjamín de Tudela described in his Book of journeys (Sefer Masaot) the existence of a holy community of wise, prudent men and great princes, at other times, especially as from the 14th and 15th centuries, the Jews of Barcelona

saw how the Jewish quarter had become a ghetto where they were segregated, confined and sometimes attacked.

This came to pass in 1367, for instance, when the main representatives of the Moorish

quarter such as Nissim Girondí, Hasday Cresques and Isaac Perfet, were imprisoned

in the actual Main synagogue and obliged to defend themselves in proceedings involving a well-known case of the

profanation of hosts by Jews in Girona.

Of the many references in Barcelona there is the unforgettable case of Montjuïc, the

Mons Judaicus or mountain of the Jews where the Jewish community buried their dead for centuries.

The internal organisation of the Moorish quarter was carried out by the Jews themselves

with self-governance confirmed by royal privilege. The community was governed by an

oligarchic regime comprising rich, learned members; the leaders were called neemanim. A council formed by ten members following the Barcelona municipal government model

supervised the management of the neemanim and controlled the executive body. Each community had the authority to enact ordinances

(taqqanot), regulations drawn up to regulate the community, religious, economic, social, educational

and ethical life of its members.

Inside the call the Jews lived according to the Jewish religious calendar, observed the Sabbaths

and religious festivals according to their laws and customs, studied classical texts

like the Bible and the Talmud, got married and divorced according to Jewish law, came before the bet din when there were quarrels and maintained their own social, religious and teaching

institutions. They also developed their culture and created master pieces which would

become part of universal Jewish literature.

The ordinances enacted by the Moorish quarter were frequently confirmed by the monarchs.

In religious terms, the community administrators had to maintain public worship, supply

the kosher food and organise burials. A court with specialised judges acting according to the

Jewish law with the consent of the monarch was entitled to pronounce sentence amongst

Jews in civil and criminal cases.

The Jews « treasure of the king», had the duty to pay taxes: every year the king required them to pay a certain amount.

The economic contribution was shared by the secretaries of the Moorish quarter amongst

the heads of households. To ensure better tax collection were created (group of Jewish quarters) which also had to pay for dinners and extraordinary

taxes when the king needed money for a war or coronation feasts. The Jews maintained

and looked after lions and other animals owned by the king.

In 1079 the Jewish population had around seventy families whilst in the 14th century

it included about four thousand people. The growth in the number of families and the

arrival of Jews expelled from France made it necessary to expand their district; Minor

Call was thus created.

The synagogue was the centre of the community; the scola where the most important feasts were celebrated (circumcision, Bar Mitzvah, the public celebration of the Sabbath, Rosh ha Shaná (New Year), Shavuot (Pentecost), Sukkot (feast of the Booths), Passover (Easter), Hanukkah (festival of Lights), Tisha be-Av (commemoration of the Temple) and Purim (feast of Queen Esther) and also the place where assemblies and meetings were held,

notices were given, trials were staged and laws were applied...

As far as work was concerned, in the call the majority of Jews were craftsmen and artisans such as weavers of silk veils, bookbinders,

goldsmiths, maker of coral jewellery, shoemakers, lenders, innkeepers and vendors; some also cultivated their

land. They were also prominent as doctors, highly appreciated by the Christians. On

the other hand, they held posts within their community: politicians such as secretary;

administrative staff such as doorman and undertaker as well as those related with

the slaughter of animals to eat, inter alia. What's more, they held religious posts

like rabbis and at the Talmudic school. And thanks to their knowledge, the most prominent

formed part of the royal court and held public office: royal bailiffs, tax collectors,

translators, ambassadors... Finally, it is worth mentioning that they made a name

for themselves in the cultural world as philosophers, men of letters, scientists and

translators and many of their works have survived until today.

During the first phase of the Jewish presence in Barcelona, the Jewish and Christian

communities maintained good relations, did business together and the count-kings entrusted

public office to Jews such as royal bailiffs, tax collector or ambassador.

Just because the call was a closed space this does not necessarily mean the Jews lived isolated. In Montjuïc,

the mount of the Jews, as well as the cemetery they possessed farmland and some houses and towers. On the

Barcelona plain they owned a lot of land, in the main vineyards, gardens, farmland

and fruit trees; some of this land they cultivated themselves and other loan collateral.

The plain area where they had the most properties were, inter alia, Magòria, Bederrida,

Les Corts, at Collserola, the outskirts of Rec Comtal... They also had houses and

workshops in Sant Jaume square and stalls at the Plaza del Blat market. Around Miracle

(the current space of Paradís Street where the Roman temple used to be) was the abode

in the 11th century of the Jewish money-changers Bonhom, Enees and David in a space

which recalled a residential area and which later was left outside the Main call area.

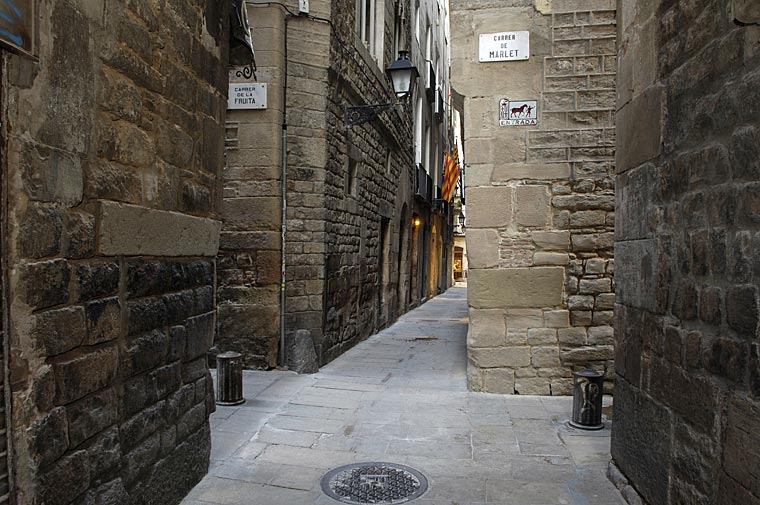

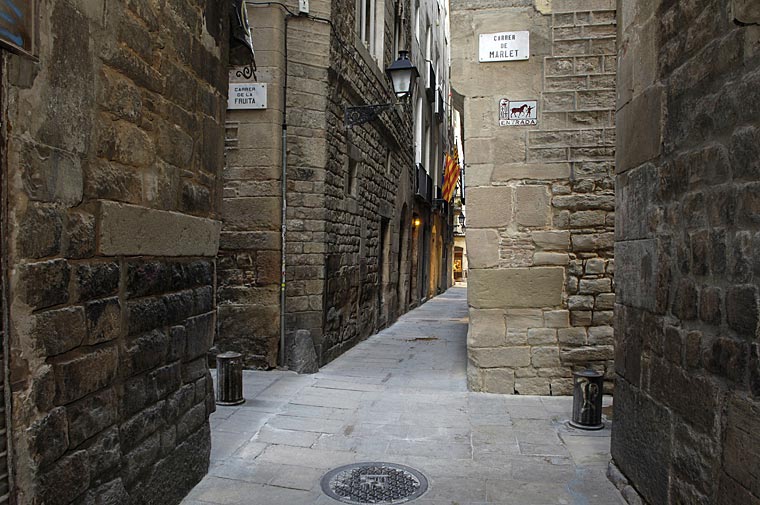

In medieval Barcelona there were two Jewish districts: Main call and Minor call, also called Sanahuja or Àngela. Main call, the oldest site of a Jewish quarter was delimited by the line of the Roman city wall between Arc de Sant Ramon del Call and Banys Nous, Call Street, the line of buildings between Calles de Sant Honorat

and Bisbe and Sant Sever. In this environment the recovery of an old Jewish building

served to house the new Call de Barcelona Interpretation Centre, maintaining Sant

Domènech del Call Street as the main thoroughfare. In addition to the Main Synagogue on Sant Domènech del Call Street there was another of the main buildings of the Jewish community, the butcher's,

where kosher meat was sold, duly purified for family consumption; the documents of the time name

the butcher's owner as David de Bellcaire and they locate the fishmonger's in the

current Fruita Street. IN 1357 the call fountain was built in the centre of Sant Honorat Street so the Jews didn't have to

leave the environs of the Jewish quarter to fetch water, whilst Banys Nous Street recalls the new baths. Banys Nous were founded

in 1160 by faqui Abraham Bonastruc, associated with Count Ramon Berenguer. The count

granted some land outside the Roman wall under Castell Nou, a place where water was

plentiful and Bonastruc had them built and equipped. According to the contract the

faqui would run them and both would receive a third of the profits. Inside was a space

intended for Mikveh . A commemorative stone on Marlet Street, a replica of that to be found at the City

History Museum, bears testimony to the foundation of a hospital at the behest of Samuel

ha-Sardí in the 13th century. In the 14th century in addition to the Main Synagogue a further four are documented, integrated in the dense social fabric in which rabbis

and academics resided (mathematicians, alchemists, geographers...) with masters of

the most varied crafts and with tax collectors and royal bailiffs.

The two calls were not connected to each other, but we believe that when the streets of Banys Nous,

Boqueria and Avinyó began to be urbanised - in other words, after the opening of the

Roman wall - the communication was much more direct. In between the two Jewish quarters

was Castell Nou (New Castle). And also equidistant between the two districts was the

Banys Nous or New Baths building which were public and not restricted on religious,

racial or gender grounds.

At the 4th Lateran Council (1215) various measures were taken against the Jews (control of lending, obligation

to wear distinctive marks on clothing etc.). In accordance with their provisions,

King Jaime I recommended the use of a distinctive mark and set loan interest at 20%;

he also forbade Jews from holding public office which entailed authority over Christians

(royal bailiffs...). However, except for the interest on loans the other provisions

were not actually implemented. Later in 1268 Jaime I allowed all Jews from the Moorish

quarter in Barcelona from wearing the circle; he only recommended that they wear a round cape when they left the city.

A further consequence of the 4th Lateran Council was the closure of the Jewish quarters

so the Christian population was separated from the Jews. However, in 1275, pope Gregory

X reminded Jaime I of the need to create districts reserved for Jews, suggesting that

this requirement had not been complied with previously. In 1285 King Pedro II promised

the nobles that no Jew would occupy the office of bailiff and confirmed the promise that no Jew could hold an office which would entail authority

over Christians. From this time on the fiscal pressure on the Moorish quarters would

increase as well as that of the doctrines of the Church against the Jews.

The arrival of orders of preachers (Dominicans and Franciscans) and the authorisation

they had to preach inside the synagogues led to various disturbances, in the main

due to the hotheads accompanying the friars and causing trouble to such an extent

that King Pedro ordered his veguers to forbid Christians from entering the synagogues except for three or four «good

men and true». He also asked the Franciscans to try and convert the Jews, not with

threats or violence, but rather using the arts of persuasion and for the Jews to hear

their preaching and not to use words which were offensive to the friars and the Christian

faith.

The epidemic known as the black death gave rise to the slanderous accusation that the Jews had poisoned the water and this

led to the outbreak of violence. On Saturday May 17th 1348 the call was attacked and several Jews were murdered. King Pedro IV asked the People for an

official declaration stating that the accusations against the Jews were merely slander

and Pope Clement VI promulgated two bulls in this regard.

In 1263 King Jaime I, at the behest of the preaching friars, convened and presided

at his palace in Barcelona over a religious dispute between Moses ben Nahman, the

rabbi of Girona on the Jewish side and Friar Pau Cristià, a convert on the Christian side.

As well as the king, St. Raymond of Penyafort and many other personalities were also

present. The debate about the two religions lasted for several days and looked at

various themes such as the arrival of the Messiah. The dispute became a European wide

event and versions have been kept in Latin and Hebrew which, self-evidently, diverge

in their conclusions. However, the dispute resulted in the censorship and burning

of Jewish books, the obligation to listen to the sermons of the Dominicans and the

exiling to Jerusalem of Moses ben Nahman.

The end of the relationship between Barcelona and its Jewish collective started in

the late 13th century, particularly after the Dispute. In 1348 the Barcelona Jewish quarter suffered its first attack and several Jews were murdered, having been accused of

poisoning the water and causing the black death epidemic which was sweeping through

the city; in 1367 the heads of the Moorish quarter Nissim Girondí, Hasday Cresques

and Isaach Perfet were imprisoned in the main synagogue for interrogation about a case of the profanation of hosts in Girona. In the late

14th century the city was experiencing a very critical situation owing to economic

decline, social movements and the municipal crises, an array of circumstances in which

the slightest spark could lead to the outbreak of violence which would turn against

the religious minorities. The fuse for the disturbance was the sermons of Ferrand

Martínez, the Archdeacon of Écija, the direct cause of the attacks on the Jewish quarters

in Seville and throughout Andalusia. The anti-Semitic movement spread throughout the

Peninsula and reached Catalonia too where almost all the Jewish quarters suffered

attacks. The Barcelona call was attached on August 5th and 7th 1391. Around three hundred Jews were murdered,

others were christened and many others took flight. Properties were attached too,

not only Jewish ones but also the Bailiff´s House.

Despite the royal attempts to restore a Jewish quarter (in the Minor call area), none was to ever take root again. In 1401 Martin I, the Human, ruled that

Barcelona would lose the right to a Jewish district.