At the Adarve del Cristo (Wall-walks of Christ) it is still easy to conjure up the first houses of the Jewish quarter settled right on the wall-walks of the wall. It would seem that both the stretch running northwards known today as Christ's wall-walks and the one heading south to connect with the San Antonio District were occupied by Jewish families.

The beauty and typicality of the Old Jewish Quarter of Cáceres, with its narrow streets, its whitewashed, luminous houses and flowers in their windows or on the balconies is only comparable with the monumental nobility of this ancient city: all serving as a symbol of the protection always sought by the protective aljamas of kings or lords. The trip from the New Jewish Quarter to the other side of Plaza Mayor also gives you a chance to visit a large part of this city which is Heritage of Humanity, following the medieval traces of its Hebrew residents.

It is not known exactly when the Jews settled in Cáceres as we have no written or archaeological sources confirming a Jewish presence in Roman times. What is for sure, as this is the interpretation given to a reading of the Charter of Cáceres of 1229, is that during the long Moslem domination of the city then called Hizn Qazris, the Jews maintained a reasonably large presence in the society of Cáceres.

The first documentation about this community dates back to the Charter of Cáceres of 1229, granted by Alfonso IX de León, but there is little doubt as to the existence of a Jewish population in the centuries of Moslem domination. The Charter of Cáceres was ratified in 1231 by Fernando III the Saint and it urged Jews, Moors and Christians to inhabit the recently reconquered city. By confirming the rights and prerogatives of the charter, the Saintly King granted Cáceres the right to organise and celebrate a fair in late April and the first fortnight of May, a market at which Jews, Moors and Christians were invited to take part as resettlers. In actual fact the Charter devoted eight chapters to the Jews who at that time barely numbered a hundred largo residents, a population which was to multiply in the two subsequent centuries. What's more, the Charter of Cáceres granted Jews' right, thanks to the royal concession, to prove their innocence by swearing on the Torah at the synagogue:

Nevertheless, although a Jew could prove his innocence by swearing on the Torah, litigation between Christians did not accept a Jew's testimony. From the Charter we can seem to deduce that in the late 13th century Jews and Christians in Cáceres not only lived physically apart, the could not enter into a mixed marriage nor was any relationship permitted between people holding different beliefs.

As far as the Jewish history of Cáceres during the 14th century is concerned, not a single document has been conserved. More than likely, according to some historians, is that there was no Jewish quarter in the city until the reign of Pedro I the Cruel during the course of a very conflictual period stretching from the start of his reign in 1350 until his death in 1369 as a consequence of the wounds inflicted on him by his brother Enrique II, something which also had major repercussions for the Jews. With Enrique II feudal and agrarian nobility gained the upper hand to the detriment of the development of the urban bourgeoisie and the consolidation of industry already noticeable in the rest of Europe, largely driven on by the Jews. With Enrique II a period of instability set in for the Jewish communities of the peninsula which Cáceres benefitted from in demographic terms as the events of the late 14th century deriving from the persecutions commenced by Ferrand Martínez, the Archdeacon of Écija, entailed a population shift which resulted in a notable increase in Jews in the north of Extremadura in view of the area's stability and the fact that the Christians in Cáceres were not as ridden by anti-Semitic prejudices, combined with the proximity to the border with Portugal which offered a way out in the event of any outbreak of violence and intransigence after the Disputation of Tortosa of 1412 and the sermons of St. Vincent Ferrer and the hate unleashed in the slaughters of 1391. In addition, Enrique II, who had started his reign in favour of the Jews, later demanded compliance with the Synod of Zamora. The Synod of Zamora of 1313 imposed the opinion of the most radical sectors of the Church, reawakening the stipulations of the Lateran Council, forbidding Jews from being doctors to Christians, excluding Jews from public office and obliging them to wear a distinctive mark of their status on their clothes.

Although in 1388 the council of Palencia stipulated the segregation of Jews and Moors in their own quarters, requiring them to sleep there despite letting them carry on business in other parts of the city, what is for sure is that the Jewish Quarter of Cáceres was also inhabited by Christian families as is borne out not only be deeds of purchase and sale, but also by some medieval Christian inscriptions right in the heart of the Jewish district. Organised as an aljama with their own governors and courts, the Jews of Cáceres worked in a wide range of trades (silversmiths, cobblers, tailors, tanners...) and some of them attained a high social standing. Also worthy of mention is the presence of some doctors like Rabbi Yuçé who practised in the second half of the 15th century.

The 15th century was a time of prosperity for the Jews of Cáceres. Except for the outbreak of violence in 1391, the Jewish quarters of Extremadura became a haven of peace for hundreds of Jews who settled in this area in the late fourteenth century, a contingent added to almost a century later by other families from Andalusia after the expulsions in 1483 of Córdoba, Seville and Cádiz. This immigrant population is what increased the number of inhabitants in the Jewish quarters of Cáceres and Extremadura from the Valle del Ambroz, Jerte, Vera de Plasencia and Sierra de Gata, in other words, the North of Cáceres. The choice of Jewish quarters in Extremadura by the new Jewish families was undoubtedly influenced by the closeness of the border with Portugal.

This migratory stream led to a real heyday of the aljamas of Extremadura. The Jewish community of Cáceres is described as an aljama in 1474 in the Repartimiento hecho a los judíos (The Forced Segregation of Jews) by Rabbi Jacob Aben Núñez, the main Jewish judge in the times of Enrique IV of Trastámara. The considerable tax contributed to the royal coffers, 8,200 maravedis, made the aljama of Cáceres one of the five largest in Castile.

In 1438 the document was signed in which Ravina, the wife of Rabbi Raime de Cáceres, sells Pedro de Carvajal, amongst other things, two pairs of hens she had in the Jewish quarter in Sant Mattheos collect and thirty years later the Jewish quarter as such is mentioned in documents which are today to be found in the Diocesan Archive of Cáceres and according to which Sayas Nahum had two pairs of houses located in the [...] Jewish quarter.

Commercial life must thus have gone on at Plaza Mayor as is borne out by many documents of the time. According to the manuscript ms. 430 of the National Library (1447), the merchant Haim Alvalía received from the Council of Cáceres a shop/house in Plaza Mayor, one of the six the Council owned in the site nearest the steps providing access to Arco de la Estrella. It was the commercial centre, the site of holidays and markets and hence the Jewish establishments abounded; a certain Samuel, the son of Dos Santo, had a shop there, and Abraham Levi or a Ruiz David alias the Jew; or the silversmith's owned by Bartholomew the Jew. The Square was not only the business and market centre, it was also a thriving crafts' centre where the trades had their workshops. During the 15th century Jewish influx to Plaza Mayor was at its height. Here the most important Jews had their properties: the Alvalía, the Nahum, the Haçan Adaroque, Isaac Navarro or Abraham Gago to name but a few of those who appear in the Diocesan Archive of Cáceres. In 1490 the interest in the commercial site Plaza Mayor was still important.

The Jews were also to be found on the outskirts of the Square: the Amarilla, notable Jews in Cáceres, had rented a house outside the Jewish quarter. Others such as Isaac Colchero lived at Pintores street, an important thoroughfare for accessing Plaza Mayor in a house rented from a Christian. Although in 1478 the Jewish quarter of the San Antonio district was dismantled and the Jews were also asked to abandon the suburbs and live at the newly assigned site, not even the abbot of the council, the main ecclesiastical authority, complied with the stipulations and he allowed the rental of properties; in 1479 a Christian rented a house to Jewish couple in Plaza Mayor for seventy maravedis and two chickens a year. In view of the lack of data in this year of 1479, it is estimated the existence of 130 homes or family units which could entail around 650 people compared with the eight or ten thousand inhabitants in the city at that time.

The new location of the aljama, driven on by Isabel the Catholic, extended via the then designated Calle de la Judería (Jewish quarter street) at San Juan collect, a narrow street stretching from Plaza Mayor to Corte street (the present Paneras street) and it had ramifications in bordering side streets and Cruz street, and where today the Palacio del Marqués de la Isla (Marquis of the Island Palace) was the new synagogue which, after the final expulsion in 1492, became a hermitage: the Cruz hermitage, alongside the street of this name. Rabbi Sergas Cohen inhabited the Galarza Palace or Casa de los Trucos. Jewish life in Cáceres did not run off closed in a ghetto but rather there was the possibility of expansion or at least easy access to the colourful area of Plaza Mayor, place where the Jews lived. In actual fact, activity was focused on this Square and on the aforementioned Calle de la Judería (Jewish Quarter street) or Judería Nueva (New Jewish Quarter).

Until the mid-15th century the aljama of Cáceres does not feature in the tax books, perhaps because it was answerable to the aljama of Trujillo in matters of a legal and religious nature. Since the instauration of the aljama, Cáceres would was full equipped: synagogue with its Rabbi and shamashim or auxiliaries like sextons, ritual bath or Mikveh whose location we are unaware of, the Rabbinic school or Talmud-Torah, the butcher's with its shojet or ritual butcher, communal oven, hospital and a shelter home for orphans and pilgrims, a Rabbinic tribunal or bet din, cemetery, plus an infrastructure for officials and managers whose blood or monetary distinction was recognised by the use of «don», a title or forbidden form of address which, as in many other cases, was not complied with in the Jewish quarter of Cáceres nor in others as in Cáceres «don» is used for the lineage of David Cohen and his wife Camila, Don Sento Cohen and doñbet dinl, but also for the cobbler don Abraham Padre, the son of don Orro; don Yudá Pardo, the dayan or judge of the aljama and don Jaro Pollo, the accountant. From these examples we can deduce that the Jewish quarter was organised around Rabbi Cohen; he had the aforementioned posts as well as that of the butler, town crier and various official duties.

As occurred in the other Spanish Jewish quarters, with the exception of those of Navarre, the edict by the Catholic Monarchs in 1492 brought to an end a long history of cohabitation, requiring all those who refused to be christened as New Christians to leave the city. Some of those who left Cáceres like Isaac Abranavel settled in towns like Segura de León very near the Portuguese border. Others went directly to the neighbouring country and in some cases continued to spread the diaspora worldwide. The surname Casseres, amongst others of local origin, bears testimony to this exile.

Adarve del Cristo

An ancient Mikveh?

Number 4 Cuesta del Marqués houses the Yusuf al Burch Museum, the translation into Arab of the name of its founder, José de la Torre, who excavated here the rainwater tank and baths on which the house was based, decorated with an abundant collections of artistic objects evoking the Arab past of the city and where you can also visit, in addition to the rainwater tank and the baths, the winery, harem, kitchen, sleeping quarters, the garden and different rooms.

The baths, the remains of a private installation, have been said to have a connection with the mikveh the Jewish ritual , perhaps shared with the Moslems, which are located in a 12th century construction. This is a natural source of water from a spring, rainwater or a well whose left wall bears a piping through which the water from the house well continuously circulated. The well water was kept warm by boilers located under the house's courtyard.

Notwithstanding, as has already been stated, it has not yet been possible to clarify whether it is an Islamic or Jewish construction, in other words, whether it actually is a Mikveh.

The mikveh, the Jewish bath of purification

The Mikveh, the Jewish bath of purification, is an essential building in any Jewish community. Its functionality is the spiritual purification through total immersion of the body in the water and this is why it accompanies all the most important acts in the life of a Jew. The Jewish woman purifies herself after menstruation when she has to have a child and when she has already had one and both the bride and the groom right before the wedding. Converts to Judaism must be immersed in the bath and also anyone who has been in contact with contagious illnesses or impurities.

The person must be prepared for the act of purification. He/she must have washed and combed first so that the water totally impregnates them. The immersion is carried out three times to ensure this is the case. Men are usually purified on Fridays before sunset before the start of the Shabbat or day dedicated to God.

Arco de la Estrella (Arch of the Star)

Excessively lowered, to the extent that in the distance it does not seem to have its actual height, the Arco de la Estrella takes its name from the Virgin of the Star whose image can be found in a Baroque shrine on the inner face of the gate, one of the four providing access to the walled city.

In the immediate vicinity of the Puerta Nueva (New Gate) from the 15th century replaced by the current arch from the 18th century, the presence of Jewish families is documented such as Haim Alvalía or Samuel ben Sem Tob at a time when the municipal ordinances did not yet require Jewish segregation.

Arco del Cristo (Arch of Christ)

The Arco del Cristo, closed in the 1st century, is the only one of the gates in the Roman wall which has stood the test of time to be with us here today. Open to the east, in the lower part of the Monumental City, for centuries it also served as the arch of the Jews, providing access to the Jewish district and possibly connecting it to the graveyard or cemetery. It is worth going outside the wall to admire the proportions of the gate and tower of Christ accompanying it.

Baluarte de los Pozos

This new tourist centre is located in the Old Jewish Quarter of Cáceres and includes a typical house, a garden-vantage point and the Torre de los Pozos (Tower of the Wells), a magnificent example of Almohad fortification, raised 6 metres above the barbican. From here you can behold some of the most characteristic and beautiful spots in the city like the Santuario de la Virgen de la Montaña (Sanctuary of the Virgin of the Mountain), Ribera del Marco stream, Concejo fountain, San Marquino… As an anteroom to the Tower the garden-vantage point has been rehabilitated.

The Tower of the Wells is the most advanced of the watchtowers surrounding the stretches of the wall. Joined to the wall by a 26-meter long watchtower pass, the majority of which has disappeared as it has been incorporated into the dwellings built in the vicinity in the subsequent period, also called the Gypsy Tower it has a trapezoid site nearing a rectangle, rising 14 metres from its base. The current entrance is gained via a wicket gate located on its southern flank which connects it to the rest of the bulwark and via which we can get into the inner chamber of the tower and from there to the upper terrace covered by groin vaults supported on a column formed by three granite tambours which is 1.84 metres high.

It has been conserved intact with various esgrafiats on its northern and eastern faces, an extremely valuable decoration not only as it features as one of the few Hispano-Moslem artistic elements conserved in the city, but also as it constitute a historical legacy of the Almohad presence in Cáceres. Whilst on the eastern and front face of the Torre de los Pozos two eight-pointed stars alternate, common in Moslem art, with false ashlar and teardrops, on the northern face there is an epigraph traced in Al-Andalus script calligraphy in which the Arabists have seen fit to interpret a religious elegy translated as God is our lord. Several metres under this esgrafiat, a knot strip is conserved framing the false and small ashlar, traces of a possible decoration based on lime mortar strips which in the past may have covered almost all the external sides of the tower.

Inside the two-storey house, around twenty scale models are displayed reproducing the civil, military and religious architecture of the city, highlighting those granted by the artist from Cáceres Eusebio Salgado. Accompanying the scale models, we can see various explanatory panels which will help us to understand the historic and urbanistic development of Cáceres.

Calleja del Moral

La calleja del Moral (Moral alley) is a small slope packed with the charm which connects the arch of Christ to San Antonio de la Quebrada street. Jewish families settled in this alley too.

Former New Jewish Quarters Synagogue (Palace de la Isla)

The Palacio de la Isla (Palace of the Island) was built in the 16th century and it currently takes up the space where the New Jewish Quarters' synagogue was located which some have said was located in one of the palace state rooms. The Stars of David in the courtyard commemorate the Jewish presence in these surroundings and the basin with Hebrew inscriptions are some of the elements which serve as a continuous reminder of this final stage of the Hebrew Cáceres collective on the eve of their expulsion.

The palace is a true gem of the Renaissance and its shields and inscriptions evoke the founding family the Blázquez-Mogollón who inscribed on the stone the motto moderata durant nobilitat animus non acta parentumor the classic uanitas uanitatum et omnia uanitasin defence of their lineage against a local branch of the family which refused to acknowledge this. However, the name of the palace can be put down to the its 18th century owners the Marquis of the Island. After serving until 1983 as the head offices of the Provincial Archive and State Library, after recent remodelling it is now used as the Municipal Historic Archive and a multipurpose cultural centre.

The synagogue

The synagogue (place of congregation, in Greek) is a Jewish temple. It faces Jerusalem, the Holy City, and it is a place for religious ceremonies, communal prayer, studying and meeting.

The Torahis read at the ceremonies. This task is conducted by the Rabbis aided by the cohen or singing child. The synagogue is not only a house of prayer but also an instruction centre as it is there where the Talmudic schools are usually run.

Men and women sit in separate sections.

The synagogue interior contains:

- The Hejal closet located in the east wall, facing Jerusalem, stored inside the Sefer Torah, the scrolls of the Torah, the Jewish sacred law.

- The Ner Tamid, the everlasting flame always lit before the Ark.

- The menorah, a seven-armed candelabrum, a habitual symbol in worship.

- The Bimah, place from where the Torah is read.

Former Synagogue (San Antonio Hermitage)

The current San Antonio hermitage occupies the plot where the Synagogue of the Old Jewish Quarters had previously stood until 1470 when the aljama, complying with the segregation order, had to grant the temple to Alfonso Golfín, the lord of Torre Arias. The latter decided to knock it down to build a hermitage on its plot under the advocacy of St. Anthony of Padua who would later lend his name to what was the Old Jewish Quarters. Subsequent to these events, a son of Pedro de Carvajal who owned properties annexed to the synagogue after the expulsion, appeared in 1504 as a donator to St. Anthony's Church:

The hermitage lent its name to the District and its main street.

The hermitage façade belongs to Barrio de San Antonio street and its rear is supported on the wall. Before its door there is an open space or square which is integrated by a portico which juts out of the hermitage. The portico has three arches, one front one and two side ones which are half-pointed but irregular, it has a sloping roof and a barrel vault with two very rough and whitewashed windows. The door is lintelled and on it there is a tile bearing the image of St. Anthony of Padua. On the pilasters there are whitewashed granite blocks and the rest is simple, whitewashed masonry.

The hermitage was transformed in 1661 and in 1975 it was restored. Between 1993 and 1994 the Municipal Workshop School remodelled its exterior and embellishment and conservation work was carried out throughout the Old Jewish Quarters: electricity and phone cables were concealed; TV cables and air-conditioning appliances were removed; waste paper baskets were installed and a solution was found for refuse collection; cracks, cornices and balconies etc. were repaired and lintels, jambs and threshold were protected.

The synagogue

The synagogue (place of congregation, in Greek) is a Jewish temple. It faces Jerusalem, the Holy City, and it is a place for religious ceremonies, communal prayer, studying and meeting.

The Torahis read at the ceremonies. This task is conducted by the Rabbis aided by the cohen or singing child. The synagogue is not only a house of prayer but also an instruction centre as it is there where the Talmudic schools are usually run.

Men and women sit in separate sections.

The synagogue interior contains:

- The Hejal closet located in the east wall, facing Jerusalem, stored inside the Sefer Torah, the scrolls of the Torah, the Jewish sacred law.

- The Ner Tamid, the everlasting flame always lit before the Ark.

- The menorah, a seven-armed candelabrum, a habitual symbol in worship.

- The Bimah, place from where the Torah is read.

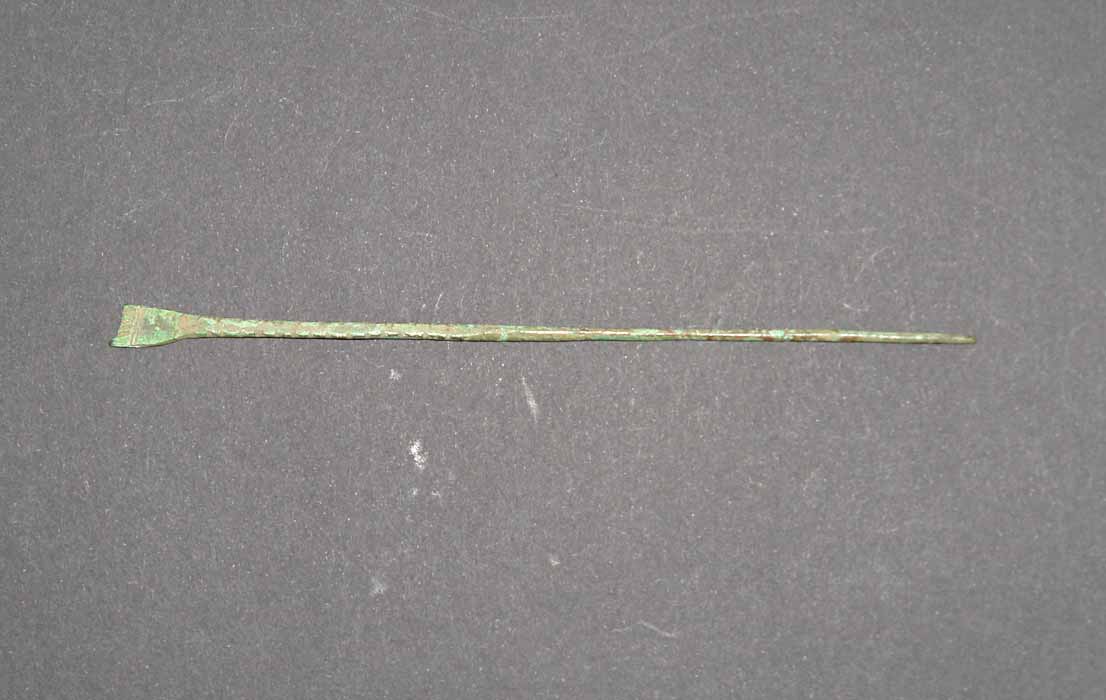

Jewish ritual pointer at Cáceres Museum

The yad, literally the hand, is a ritual pointer used to follow the reading of the text of the Torah. This pointer, currently located at Cáceres Museum, was found in the excavations of Parador de Plasencia in 1996.

The pointer at Cáceres Museum is a bronze piece which prevented the Torahparchment from being touched whilst reading. This measure was taken to preserve the fragile support which is parchment and which sometimes did not absorb ink properly and this could run if the finger moved above the letters.

Main Square

Plaza Mayor, the anteroom of the amazing Monumental City which Cáceres holds within its walls, symbolises the frontier between the Old Jewish Quarter and the New Jewish Quarter, between the traditional Jewish site within the walls in the steepest part of the Romana and medieval city and the new winds of the 15th century in an expansion of the city which the Jews would end up being excluded from.

A meeting point, a place of transit between the hustle and bustle of the new city and the withdrawal of the previous one, Plaza Mayor opens out onto the walled site through the staircases which rise to the Arco de la Estrella (Star Arch), framed by the 18th century hermitage of la Paz on the left and by the Torre de los Púlpitos (Pulpits Tower) from the 15th century on the right.

New Jewish Quarters

The New Jewish Quarters emerged after the decree of 1478 in which the Jews of Cáceres were ordered to gather in a single district outside the walled city. The area selected for this New Jewish Quarters was to be the square delimited by the current General Ezponda street, Concepción square, Paneras street and Plaza Mayor with Cruz street serving as the main thoroughfare thereof. Something still remains in Cruz street, long called Jewish Quarters street, of the atmosphere of that new Jewish district which existed in this form for only fourteen years, though some its settlers remained connected with the area for longer now as New Christians.

Olivar de la Juderia

Through the Mérida Gate, coming out of the Monumental City and leading to Santa Clara Square which takes the name of the 18th century Clarisas Convent, a narrow alley leads to the Mochada Tower, a watchtower from the 13th century, filled with mud, which strengthened the city's defences in times which were still unstable and which today has been consolidated and recovered as part of the medieval city. Going round it via the gardens right alongside, you reach hat is known as the Olivar de la Judería (Jewish Quarter Olive Grove), a recondite garden which belonged to one of the Jewish houses situated at this end of the city.

Pereros Street and Square

Pereros street gives out into Pereros Square which marks the limit of the traditional Jewish quarters. At Pereros square, a plaque recalls that in 1477 the Jews sought out Queen Isabel to ask for greater fairness in the distribution of municipal taxes, and their request was made at a time when there were 130 Jewish families in a total population of 8,000 inhabitants. Once again, as the Jewish city comes closer to the high city, the typicality of the whitewashed houses and modest proportions is gradually replaced by the nobility of the stone houses like that of Pereros from the 15th to 17th centuries which forms a corner between the street and the square bearing its name and which currently houses the Colegio Mayor Universitario Francisco de Sande (University College), a branch of the Provincial Delegation. The square also overlooks the house of Sánchez-Paredes from the 16th century, connects to the end of the wall, solidly protected by the towers of Mérida to the south.

Rincón de la monja

Rincón de la Monja street, as far as its connection to Casa de los Caballos, takes up the whole western flank of the Jewish quarter and the San Antonio district lies below. It is beautiful paved street inaugurated with the splendid presence of the house of Durán de la Rocha with its noble coats-of-arms and its mats protecting the windows and which winds up to the high part of the city, adapting to the terrain and leaving behind it some quite charming spots.

Despite the fact that in this section of the Jewish quarter numerous whitewashed houses can be viewed, stone buildings do still predominate though, some of them settled on the same original rock such as the Compañía de Jesús Convent from the 18th century. Finally, the rear part of the Veletas Palace is joined via an arch to Casa de los Caballos, with both spaces forming part of the Cáceres Museum, the first as the centre for archaeology and ethnography sections (in addition to the spectacular rainwater tank of the former fortress) and the second serving as the fine arts' department of Cáceres Museum where works by Miró, Picasso, Tàpies and Canogar can be viewed as well as the magnificent Jesús Salvador (Christ as Saviour) by El Greco. The museums' pieces also include some references to the Jewish world such as the famous yad or Plasencia pointer.

San Antonio de la Quebrada District

The Old Jewish Quarters of Cáceres is one of the most beautiful areas in the city within its walls. The urbanistic interventions have been small in scale over the centuries and the current San Antonio de la Quebrada district today conserves a large part of the structure and typicality it must have had when settled by Jews. Its haphazard, steep streets; the simple whiteness of its whitewashed houses; its seasonal flowers on balconies and little gardens and the daily life it houses from a strange contrast with the severe, monumental structures which crown it, the ochre colour of stones bathed in sunlight. Its adaptation to the orography, as it is located in the hilliest area of the walled city, is one of the most string characteristics of the Cáceres Jewish Quarters where the streets and houses form a very varied set packed with nooks and crannies, steps and fanciful spaces which its current residents conserve, adorning them with the flowers of the season and rife with popular flavour.

The streets of the Cáceres Old Jewish Quarter have marked slopes and hills which sometimes have steps as they form that part of Cáceres within the walls which is most difficult to urbanise and this has led to a place containing poor constructions, and its intricate spaces also distance it from the circulation of the major nuclei of the city.

The houses back onto the wall and use it as one of their own and some towers and other spaces as rudimentary gardens or improvised fruit and vegetable patches, combing nature and history with what is popular, something which already occurred back in the 18th century when it was allowed to use the wall for other purposes in view of the fact that it could no longer be used for defensive purposes. They are small houses with one storey or a ground floor and another upper floor, small, haphazard openings and with the majority of the doors lintelled.

San Antonio de la Quebrada Street

After the wall-walked parapet round the wall-walks of the wall, the San Antonio district extends around the intricate street of the same name which winds into streets and alleys, taking up a major part of the south-eastern flank of the city. Its first stretch emerges in a fanciful urban space around which a nucleus of whitewashed houses distributed with landings, steps and some lintelled doors which overlook the current Ermita de San Antonio (St. Anthony's Hermitage). Further on the buttresses of the Casa de los Caballos re-connect the Jewish quarters with this property which includes the Fine Arts' section of Cáceres Museum. At the end of a small street emerging on the left is the Torre de los Pozos, recently restored and encompassing an interpretation centre right in the heart of the Cáceres Jewish quarters.

San Jorge Square

To reach San Jorge Square, marking the north-western border of the traditional Jewish quarter, you first have to pass by the monumental Santa María Square, a unique set of 16th century constructions where the Mayoralgo palace, the Ovando palace, the Carvajal tower and palace, the house of the Dukes of Valencia and the Procathedral of Santa María - at whose corner the mystic San Pedro de Alcántara indicates the way to the heart of the city - can all be found. San Jorge Square, bordered to the north by the 15th century Golfines de Abajo palace and to the south by the presence at a height of the San Francisco Javier or Compañía de Jesús Church rom the 18th century, is an amazing space organised into various levels which interconnect by way of steps. It is one of the spots of Cáceres which has the most personality. In its lower part in an easterly direction there lies the Cuesta del Marqués, one of the main communication thoroughfares between the Old Jewish Quarter and the rest of the city.

Stars of David

At number 30 of Barrio de San Antonio de la Quebrada street two stars of David can be seen adorning the street and recalling the Jewish past of the San Antonio District.

Glossary

- jewish quarter: Traditional name given to the Jewish district or part of a city where the Jews´ homes were concentrated. In some cases it was determined by law as an exclusive place of residence of the members of this community. By extension, the term applies to any area known to be inhabited by families of Jewish culture.

- mikveh, l. heb: Ritual bathing. Space where the purification baths prescribed by Judaism are taken.

- rabbi, l. heb: A man instructed and ordained in the law who can spiritually lead a community. It literally means ‘master´.

- torah, l. heb: Text of the first five books of the Bible.

- wall-walk: Path around a city wall or parallel to it. In medieval Islamic cities it is the cul-de-sac which leads to private homes and which is closed at its entrance.

- aljama, l. heb: Specific institution of the Medieval Hispanic kingdoms which dealt with the governance and internal administration of the Jewish community.

- collection: self-governing Jewish organisation which brought together several aljamas for economic reasons the distribution, valuation and collection of taxes to be submitted to the king.

- diaspora, l. gr: Dispersion. A Word of Greek origin which means ‘exile´ and designating the dispersion of the Jewish people worldwide.

- maravedis: Tax in force between the 13th and 18th centuries in the kingdoms of Valencia and Majorca by James I under the statute of April 14th 1266 and it consisted of payment of seven royal sueldos of Valencia (one maravedi) every seven years for each dwelling which had property valued at fifteen maravedis or more.

- shamashim, l. heb: At the synagogue, a paid official who serves as an auxiliary to the hazzan (kantor).

- synagogue, l. gr: Gathering place for faithful Jews and the place of worship and studies. The term comes from the Greek synagogē which means place of congregation.

- yad, l. heb: Lit. Hand. A pointer which is used to follow the text without touching the Torah scroll.