In Calahorra the Mikvehor Jewish ritual bath is documented as can be deduced from a note in the minutes of the Cathedral chapterhouse of this city in which the chapterhouse granted a license to the Jew Simuel Matron to sell the guerta del vañadero de las judías. In all likelihood it is a fruit and vegetable garden whose income was used to pay any expenses caused by the maintenance of the Mikveh.

Erected on the former Celtiberian and Roman citadel which forms an irregular circle at one of the two hills on which Calagurris was raised, historic Calahorra, the Calahorra Jewish quarter stands out for its disturbing curved streets, many of them culs-de-sac, its low houses with a back yard and its sudden exits to vast vantage points onto the valleys of the Ebro and Cidacos, breaking by surprise the closure of an almost cryptic location. In this humble district, a true city within a city, the Jews of Calahorra resided for at least five centuries, though it seems to have been proven that they settled here well before that time.

Calahorra's strategic position, firstly, opposite Al-Ándalus and also the kingdom of Navarre, the fact it is on the Jacobean Way of the Ebro, the richness of its agriculture and the very commercial dynamic of the city have meant that the Calahorra aljama managed, in the 15th century, to become first in La Rioja, even surpassing the Jews of Haro who were regionally predominant during the majority of the Middle Ages. In this century the Calahorra Jewish quarter had around six hundred people after a long growth process during the three previous centuries. The first documents attesting to the Jewish presence in the city date back to the 11th Century and they bear testimony to buying and selling activity which was protagonised by Jews, something which was a constant throughout the Middle Ages as is reflected in the important documentary corpus related with Calahorra which has been conserved at different archives.

In the Middle Ages Calahorra was a frontier city, a relatively populous place with an important Jewish quarter. The Ebro formed the frontier between the kingdoms of Navarre and Castile, but it was also a privileged route for trafficking men, ideas and goods which encompassed a considerable density of Jewish inhabitants in the 13th and 15th centuries.

The Jewish presence in the lands of the Medium Ebro Basin dates back at least to the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD. In the Edict of Caracalla of 212 the Jews of Calagurris were regarded as citizens subject to Roman Law. Under the reigns of the Visigoths and the Moslems, the city went about its business peacefully until the 10th century. Sancho Garcés I of Pamplona occupied Calahorra until 914; in 918, with the aid of Ordoño II, he recovered the city which the Moslems retook in 968. In 1045 Calahorra became a permanent part of the Christian domain under the aegis of García III of Navarre..

When in 1076 Calahorra and the lands of La Rioja were occupied by the Castilian king Alfonso VI, its settlers received confirmation of their former charters, habits and customs. With the Castilian conquest, Calahorra had also become a stronghold on the border with Navarre. This new status convinced the Castilian kings to promote the settlement of new inhabitants in the city by granting new privileges.

In the second half of the 11th century the first news arrived about Jews residing in Calahorra, tracked in purchase and sale agreements or exchanges of farms in which they featured as contracting parties or witnesses.

Following the general trend in Castile between the mid-11th century and the mid-14th century, the Jewish community of Calahorra experienced an age of growth and splendour spurred on by the favour and protection afforded by the kings who were aware of the major role the Jews could play in the resettlement and social organisation of the territory. This long period of prosperity for the aljamas of La Rioja is best illustrated by the granting of specific charters to Jews. Concurrently, the role of the Jews in the social life of Calahorra became increasingly important to such an extent that in the second half of the 12th century, some Jews in Calahorra feature holding public offices as a merino which involved economic administration and the collecting of rents for the council. In the same way, in the 12th and 13th centuries many Jews from Calahorra are cited in documents as the owners of farmlands, vegetable and fruit gardens and vineyards, demonstrating their healthy socio-economic status. As regards the rural property purchase and sale documents involving Jews from La Rioja, worthy of special mention owing to their exceptional nature are the six documents written in Hebrew which are conserved in the Calahorra Cathedral Archive pertaining to dates falling between 1259 and 1340 which is, undoubtedly, the period of greatest splendour of the aljama in Calahorra.

Concurrently with their material prosperity, the Jews who resided in Calahorra also enjoyed reasonable integration into the population as a whole, at least during the first decades of the 14th century. In 1320 the Jews, along with the nobles, clerics and cathedral chapterhouse and everyday folk, took part in the construction of some water mills in the municipal district of San Adrián, taking advantage of the waters of the River Ebro. The Jews contributed 750 maravedis, 7.5% of the total amount collected which stood at 10,000 maravedis. The Calahorra Cathedral Archive also holds a fascinating book of oaths dated 1324, containing the oath which Jews had to make in those legal acts in which they were involved, yet further evidence of the growing economic power of the Hebrew community in Calahorra.

During the 13th century the Calahorra aljama was the most important, most populated of the Jewish communities in La Rioja, even surpassing the Haro aljama - the main aljama at the turn of the century - in terms of its importance. At the end of the century the total Jewish population in the city stood at 450 to 500 residents, 15% of the population, a very high percentage and an indication of the relevance of the Jewish community. In spite of everything, it seems highly likely that the number of Jews residing in Calahorra was even higher in the mid-14th century, coinciding with the time of greatest splendour in the Calahorra aljama. The following can thus be deduced from the amounts that the Jews of Calahorra satisfied the cathedral chapterhouse by dint of the income known as the Treinta Dineros (Thirty Pieces of Silver whereby the use of the external signs of identification worn on their clothes was repaid (the reddish circle which they had to wear on their attire on their right shoulders): each married or single male Jew aged over twenty was obliged to pay thirty pieces of silver per year in this regard to the Cathedral chapterhouse. Thanks to the registration in accounts of this tax, we know that in 1329 the Calahorra Jews paying this tax numbered between ninety three and a hundred.

This climate of prosperity of the Jewish aljamas in La Rioja and the relative friendliness of Christian-Jewish relations was cut short by the fratricidal war which saw King Pedro I and his stepbrother Enrique de Trastámara engage in battle for the Castilian throne. Some Jewish quarters of La Rioja were attacked between 1360 and 1369 and once the war was over, the Jewish population of Castile suffered the Anti-Semitic measures decreed in the early years of the reign of Enrique II as well as the consequences of the Black Death and poor harvests. Under these difficult circumstances, some groups of Castilian Jews, mainly from Calahorra, emigrated in around 1370 to the kingdom of Navarre where they were favourably received by Queen Juana, the wife of Carlos II (Charles the Bad) who took them under their protection and granted them various tax breaks.

The situation was considerably exacerbated at the time of the persecutions which were inflicted in 1391 on many Spanish Jewish communities, though everything would suggest that this was no better or worse in Calahorra. There is thus only documental reference to the attack suffered on the Logroño Jewish quarters which was announced in the Crónica (Chronicle)of King Enrique III in Sebet Yehudah, a Hispano-Hebrew chronicle from the 16th century and in some anonymous Hebrew kinot.

The recovery of the Castilian Jewish communities from their slow decline commencing in the second half of the 14th century took place as from the reign of Juan II, largely thanks to the decisive action of the Constable don Álvaro de Luna, the King's favourite and a firm protector of the Jews. However, the recovery was very slow to such an extent that in 1439 Calahorra obtained the royal privilege of a discount of 24% and instead of paying 5,202 maravedis of old money actually settled around 4,000, amounts they had to pay to the royal finances by way of a tax because, as has been described in Escribanía mayor de Income Clerkship, there were poor people.

The second half of the 15th century was characterised by the development of progressive more intolerant policies by the council to the aljama, fostering a climate of growing tension in the relations between Christians and Jews. This course of events was closely connected with the every greater pressure of the Royal Courts on the Jews and since the mid-13th century they had constituted one of the spearheads of antisemitism in the Castillian kingdom. The debate in the Courts about the Jews was mainly focused on the regulation for lending contracts and the suitability of proceeding with the social segregation of Jews and hence the monarch was continuously asked to force the Jews to wear the distinguishing signs on their clothes and to be restricted to isolated urban sectors and to forbid them from exercising certain professional activities and the acquisition of real estate. These provisions culminated in the Valladolid Ordinance of 1405 and, in the main, in the Laws of Ayllón of 1412 which set out to make the Jews' life as difficult as possible to ensure their rapid conversion to Christian it or, failing that, their exile from the Kingdom.

Under the reign of Enrique III, the Ordinance of Valladolid in which the Jews were almost the sole cause of the meeting, hardened the royal policy towards the Jews, perhaps brought about by the King's illness and the poor economic climate. In any case, its content brought nothing new as it merely borrowed from laws already approved in the Ordinance of Valladolid of 1348 and those assumed by Enrique II and Juan I. The Jews were required to wear distinguishing signs of reddish cloth, the prohibition of usury and, in recompense, permission to devote themselves to agriculture, but, in particular, the revocation of all the legal privileges they still enjoyed. And the order was renewed to wear a kind of red circle as a distinguishing feature when travelling through towns and cities.

A further step towards the harassment of the Jewish population was the law segregating the Jews and Mudejars of Castile into isolated districts which was enacted in the Courts celebrated in Toledo in 1480. A maximum timeframe of two years was now agreed for all Jews and Mudejars to withdraw to an urban area which was separate from the Christian population with a view to avoiding the religious proselytism of Jews and mudejars amongst Christians, particularly amongst those who had recently converted to Christianity. As early as 1412 the Laws of Ayllón had stipulated the segregation of the Jews into isolated districts despite the fact that this provision was never strictly adhered to. In 1455 there was an attempt to isolate the Jews in the Haro Jewish quarter, promoted by the municipal authorities and backed by the Count of Haro and something similar occurred with the Mudejar collective there in 1464. However, these provisions were only really effective after their approval by the Courts of Toledo in 1480. Compliance with the segregation law gave rise to many conflicts, making it clear how impossible it was to reach an agreement between two communities which were already at loggerheads.

In the quarrels occurring between the council and the aljama, the King's Justice always argued that the legislation issued by the Courts should be respected so in December 1491 the Catholic Monarchs ordered Don Juan de Ribera, the Captain General of the Navarre border and the Chief Magistrate in the cities of Calahorra and Logroño and the town of Alfaro to require Jews to wear the distinguishing signs on their attire. This charter was granted at the request of some residents in Calahorra who had complained that some Jews failed to comply with these laws, alleging that they were exempt owing to their status as collectors of excises, tithes, services and tributes for transhumance.

The decree of Expulsion of 1492 brought about major losses to the Jews of Calahorra as well as of those of the other Jewish quarters of Castile and Aragón. Diego Martínez, a converted Jew who in September 1495 went back to Calahorra after the expulsion after converting to Christianity, claimed some vines and a fruit and vegetable garden which he had sold when he left Castile, a sale in which sale was wronged in three parts less half of the fair price. Notwithstanding, the circumstances differed from case to case. For example, Simuel Matron, a Jew residing on Calahorra, obtained on June 2nd 1492 a license from the dean and chapterhouse of the Cathedral Church of Calahorra for the sale of rustic properties (a fruit and vegetable garden, an olive grove and a vine) which he had in Torrecilla in the municipal district of Calahorra, on the sole condition that he did not divide them when selling them and that he would pay any sales' duties stipulated, comprising one maravedi for every fifty he obtained. However, on the same day, the properties of Abraham and Çag Cohen, also Calahorra residents, were seized by the chapterhouse until all the amounts had been paid which were outstanding on the occasion of the rental of the Tercias of Arnedo (income tax), Quel, Autol, Miro and various other places in La Rioja.

The decree of Expulsion did not achieve the homogeneous fusion of Christians and converted Jews. The Catholic Monarchs waged a fierce evangelization campaign amongst the Jews with a view to seeking their conversion to Christianity in as large numbers as possible. This campaign was stepped up shortly afterwards amongst the converts to seek their more complete Christian instruction, but there is no doubt that during the early decades of the 16th century, many of the recent converts were almost totally in the dark about the Christian religion. And neither did they achieve the desired social fusion owing to the climate of scepticism, suspicion and reluctance with which the old Christians greeted the Jewish converts. The Jewish problem became a convert problem.

Ancient Mikveh

The mikveh, the Jewish bath of purification

The Mikveh, the Jewish bath of purification, is an essential building in any Jewish community. Its functionality is the spiritual purification through total immersion of the body in the water and this is why it accompanies all the most important acts in the life of a Jew. The Jewish woman purifies herself after menstruation when she has to have a child and when she has already had one and both the bride and the groom right before the wedding. Converts to Judaism must be immersed in the bath and also anyone who has been in contact with contagious illnesses or impurities.

The person must be prepared for the act of purification. He/she must have washed and combed first so that the water totally impregnates them. The immersion is carried out three times to ensure this is the case. Men are usually purified on Fridays before sunset before the start of the Shabbat or day dedicated to God.

Ancient synagogue

After the Jews left Calahorra, the Catholic Monarchs, in a charter granted in the town of Ágreda on August 7th 1492, made a donation to the Cathedral church of Calahorra of the building which had, up to that point, been the Jewish synagogueso as to recondition it as a Christian church. The chapterhouse transformed the building, situated in the vicinity of the church of San Salvador and the castle, in a hermitage dedicated to San Sebastián.

Some decades later, in 1579, the Cathedral chapterhouse granted the church of San Salvador to the Franciscan friars who reformed it and extended it with a cloister. Since that time, it changed its advocacy of San Salvador to that of San Francisco which is still retained. With a view to building the cloister, the chapterhouse also granted the San Sebastián hermitage to the Franciscans, in other words, the old synagogue building which was knocked down.

Everything would suggest that the synagogue would take up the space where, in 1927, the Aurelio Prudencio School unit was erected in 1927 (now the «San Francisco» Adult Education Centre) at Rasillo de San Francisco Square on the cloister of the church of San Francisco, in ruins in all likelihood since the Mendizábal Disentailment in 1835. This school unit also occupied an alley known, significantly, as Callejón de la Sinagoga (Synagogue Alley), about which news was also provided in 1925 by Father Lucas de San Juan de la Cruz in his study on the city of Calahorra, indicating it as the core of the old Jewish quarter.

The synagogue

The synagogue (place of congregation, in Greek) is a Jewish temple. It faces Jerusalem, the Holy City, and it is a place for religious ceremonies, communal prayer, studying and meeting.

The Torahis read at the ceremonies. This task is conducted by the Rabbis aided by the cohen or singing child. The synagogue is not only a house of prayer but also an instruction centre as it is there where the Talmudic schools are usually run.

Men and women sit in separate sections.

The synagogue interior contains:

- The Hejal closet located in the east wall, facing Jerusalem, stored inside the Sefer Torah, the scrolls of the Torah, the Jewish sacred law.

- The Ner Tamid, the everlasting flame always lit before the Ark.

- The menorah, a seven-armed candelabrum, a habitual symbol in worship.

- The Bimah, place from where the Torah is read.

Balcony on Cabezo street

Following the layout of the Murallas street, inside the citadel, the itinerary takes us to via San Sebastián street to the maze of Cabezo street which comes out onto a large balcony, with its lamp-posts and railings, open to the traveller on the close-packed house of the Moorish quarter which extended to Arrabal street and, at the back, over San José Discalced Carmelites convent, constructed when St. Teresa was alive, which practically defines the city limit with the Ebro Valley. Part of Cabezo street winds on its merry way, following the wall-walks of the old wall until reaching Morcillón street at the crossing with the cuesta del Horno slope.

Calle de los Sastres (Tailors' street)

Sastres street, backing onto Castellar, recalls one of those activities traditionally related with the Jews in Sefarad.

Once again the curves, more characteristic of the Celtiberian strongholds, which with Roman quadrature, afford the greatest charms of this street where the houses are higher and end on the cathedral slope.

Calle del Horno (Oven Str.)

In Calahorra the existence of a bread oven for the Jewish quarter is documented, having been bought by Pedro Sánchez Roldán after the Jews left the city. The location of the oven is unknown in any case.

The oven

During the Middle Ages the ovens of the cities were of a public nature and could only be built or used under royal license. It was the norm for there to be at least one oven in each Jewish quarter at which bread was baked for daily consumption.

From an architectonic perspective, the Jewish oven had to be similar to those raised in other parts of the city: Making bread was not subject to any specific kind of ritual and hence the oven was not subject to any different aspect in its construction. This also means that a Jew could buy bread from a Christian or use a Christian oven to bake bread without transgressing any rules.

During the Passover unleavened bread was baked (matzah), without yeast, whose dough bore a seal. As it was a special kind of bread, in Jewish quarters where there was no oven, temporary ones could be built to bake it.

Cathedral

Contrary to what is a rooted tradition in many Spanish cities, in Calahorra the madinat al-Yahud, or city of the Jews, is situated in the acropolis of the city alongside the castle and the Salvador church, whilst the cathedral takes up the lowest territory thereof on the banks of the river, subverting the traditional geographic distribution of power.

The sole reason is the unbreakable link maintained by the Calahorra cathedral with the place where the martyrdom of the saints Emeterius and Celedonius occurred in the 4th century, an episode which had a major religious impact even defining the patron saint of a city as distant as Santander was where, according to Christian legend, the heads of the martyrs arrived which the Roman soldiers had thrown into the river, furious because the miraculously kept talking to each other even though they had been separated from their bodies... The magnificent cathedral of Santa María was founded on the banks of the River Cidacos between an Episcopal Palace and Paseo de las Bolas, whilst Santiago church, in the upper part of the city, played the traditional role of the great Christian churches.

The current cathedral started to be raised in the 15th century and at this time a long process started which would not end until 1904 when the retable of the main altar was placed, replacing the previous one which had disappeared because of a fire. Behind its façade with Neoclassical Baroque elements, the main gate opens out onto some steps which go down to the lower level where the former churches must have been on which the cathedral was erected. In the latter, in addition to the vast space dedicated to the martyrs, the retable of the Monarchs stands out in the retrochoir; the magnificent Gothic baptismal font, placed in the exact spot where, according to tradition, the martyrdom of Emeterius and Celedonius took place; the Virgen del Pilar chapel with its two retables and with the tomb of the famous bishop don Pedro de Lepe, the one who gave rise to the expression sabes más que Lepe (you know more than Lepe); the plateresque St. Peter's retable made of alabaster; the small Sacristy Mirrors Room or the numerous treasures displayed in the Diocesan Museum.

The relationship between the Chapterhouse and the Aljama

The power of the Jewish collective and its relations with the Church are borne out by the long dispute between the aljama and the Cathedral´s chapterhouse because of the numerous possessions of the Jews of Calahorra who, owing to their very status as property of the Crown, were exempt from paying the tithes incumbent upon the Christians.

Despite the decree by Alfonso VIII which required them to pay the tithe, the refusal by the Jews brought about the promulgation of a bull by pope Innocent IV demanding that share proportional to the Chapterhouse.

El Sequeral Tower

The El Sequeral tower closed off the Late Imperial Roman wall to the southeast (1st century AD). It's well worth going down a few metres to the same tower base and taking a closer look at the complex series of walls and defences which existed in this part of the city where the tower must have made a major visual impact on those arriving at the former Calagurris Iulia on the Roman road from Gracchurris (Alfaro) or from Caesaraugusta (Saragossa). A milestone where the mark of the Jews of Calahorra with that of their Roman forefathers converge, some of them as illustrious as Marcus Fabius Quintilianus or the poet Aurelius Prudentius.

Jewish cemetery

After the expulsion in 1492, the Catholic Monarchs granted several residents of Calahorra the headstones and stone of the Jewish cemetery of this place. Very shortly afterwards, and with a chorus of complaints from the council authorities, the Royal Council clarified that the concession made to some residents of Calahorra solely referred to the cemetery stone, but in no way to the plot which was to be used by the municipality. It was also absolutely forbidden for the beneficiaries of the stone to build on the plot or to fence it off.

The cemetery

The cemetery was located outside the walls at a certain distance from the Jewish district. The chosen site:

- Must be on virgin soil

- Must be on a slope

- Be oriented towards Jerusalem

The Jewish quarter had to have a direct access to the cemetery to prevent the burials from having to pass through the interior of the city.

After 1492 the monarchs authorised (in Barcelona in 1391) the reuse of stones from Jewish cemeteriesas construction material. It is thus not unusual to find fragments of Hebrew inscriptions in several subsequent constructions.

Despite the pillaging they suffered from the late 14th century, the memory of these cemeteries has remained in the name in certain places, for instance, Montjuïc in Barcelona or Girona. We are aware of the existence of more than twenty medieval Jewish cemeteries. Others are only known of thanks to the documentation or the headstones conserved. The one in Barcelona at Montjuïc was excavated in 1945 and 2000, the one in Seville in 2004, the one in Toledo in 2009 and the one in Ávila in 2012.

Morcillón Street

The route goes back to Morcillón street, another fine example of a cul-de-sac, in this case forked into two small alleys which don't lead anywhere. Even so, it is worth following it to the end to discover, amongst its houses, architectonic details which reveal the overlaying of remodelling in the district which has maintained its humble status over the centuries or, if you're lucky, the interior of some of the many houses in the environs which, behind the entrance hall, possess an inner courtyard where family life could go on away from the gaze of onlookers...

Murallas Street

At the vantage point on the right there emerges Murallas street which runs along the layout of the former Roman enclosure, partially replaced by a row of houses on the right. However, part of the old wall appears at the end of the first section of this street which culminates in a new vantage point, opened when a building disappeared on the hillside which, in this case, overlooks the cathedral and the bridge over the River Cidacos with the silhouette of Moncayo in the background. The vantage point is situated as a point of archaeological interest on which the El Sequeral tower is located, which closed, Late Imperial Roman wall to the southeast (1st century AD).

Planillo de San Andrés

A narrow passage connects Morcillón street to the vast open space of Planillo de San Andrés, very near Cuesta del Horno street, recalling that the Calahorra aljama in addition to its synagogue or butcher's, had its oven, vital for making the traditional unleavened bread form religious feasts. At this square, in addition to the Roman arch of Planillo, the original San Andrés church stands, the product of the setting up of a 16th century Gothic temple over a previous 6th century church destroyed by the Arabs and making an important architectonic contribution in the 18th century. Its curiosities include a tympanum decorated with a cross with different arms which is interpreted as the triumph of the Christian faith over paganism and Judaism, with the latter illustrated by a synagogue.

On the left of the square a small labyrinth of four culs-de-sac is the perfect evocation of the medieval layout of the Jewish quarter with an urban sprawl of houses with entrances and exits via different places.

Portal de la Judería

In all likelihood this is the area called Castellar which, in 1336, the aljama obtained from the chapterhouse by way of an exchange as well as the Cantonera tower and part of the torre Mayor, with the authorisation to raise the wall-walk inside the Jewish quarter should they so wish because the Jewish quarter is stronger.

The Jewish quarter was totally surrounded by a wall in which at least one gate was opened as is stated in various documents from the 15th century in which reference is made to the so-called Jewish Quarter Gate which connected the Jewish quarter with the other quarters of the city.

The curves, imposed by the topography, are once again the main feature of this layout which halts at the confluence of Cabezo street with Deán Palacios and Sastres streets. It was here that the main entrance or Jewish Quarter gate was situated which had its main point of access in Deán Palacios street.

Rasillo de San Francisco

Rasillo de San Francisco, a broad platform in the heights of the citadel - which currently includes the church of the same name and all its environs - was one of the oldest sites of the Calahorra Jewish Quarter, formed in the shelter of the castle and San Salvador church (today, San Francisco), probably of late Roman origin.

The synagogue must thus have operated here at least between the 14th and 15th centuries until the Catholic Monarchs granted the building to the Chapterhouse after the Jewish expulsion on August 7th 1492. The Jewish temple was turned into San Sebastián hermitage, located alongside San Salvador church and the castle. In 1579 the Chapterhouse granted the church and hermitage to the Franciscans who turned it all into a convent, erecting the chapel of the Santísimo (holy sacrament) at the place where Friar Juan de Jesús María was born, better known as el Calagurritano (the man from Calahorra), an illustrious barefoot Carmelite and the first biographer of St. Teresa of Jesus, uncorrupted and venerated in Montecompatri (Italy), Calahorra's twin city. Behind the convent ruins, which after the Disentailment was successively used as a prison, court, school and institute, the church was desacralized and is currently granted to the Brotherhood of Santa Vera Cruz which takes up the only wing of the cloister which is conserved), as well as housing the Museo de Pasos (Museum of Passages) of a Easter Week declared as being of regional tourist interest.

San Sebastián street

Alongside the Rasillo de San Francisco at the confluence of Deán Palacios and San Sebastián streets, there appears the Deán Palacios Cultural Centre, a centre for various municipal areas in a block shared with the adult education centre and the municipal music, dance and ceramics school. San Sebastián street, going all around the block, is one of the most beautiful, unique ones in the Jewish quarter; it may well be worth going down it for a few metres on the right stretch to overlook the Jewish quarter plot on the left of the access to the Deán Palacios centre; here the street curves sharply, characteristic of the Calahorra citadel which gradually reveals a row of small houses endowed with a popular design.

The bricks and gates of these houses recall the fact that one of the Jews' activities in Calahorra was farming, along with commerce and crafts, though some members of the aljama, such as the illustrious physician (doctor) Yom Tob or the members of the Zahac de Faro family, were notable figures in the city and beyond its limits. These activities enabled the Jewish collective to achieve strong purchasing power as is borne out by its constant bidding for ecclesiastical income or their incessant buying and selling of houses and land. The economic prosperity of the Jews of Calahorra shows that several historians locate in Qalʼat al Hajar, the Moslem Calahorra, the death of the traveller and scholar from Tudela Abraham ibn Ezrá in around 1167 after having travelled all around Europe. The second street emerging on the left from San Sebastián street does so from the small square formed in the change in direction of its route and turns in determined fashion to the open space of a vantage point at the above a former city wall. From here there are good views of the sanctuary of Virgen del Carmen, the patron saint of Ribera, on the other side of the river.

Abraham ibn Ezrá

Abraham Ibn Ezrá (c. 1089-1167) spent his youth in al-Andalus (in Córdoba, Seville and Lucena) where he trained in Jewish culture in Arab.

In around 1140 he decided to abandon Sefarad to travel around the North of Africa, probably in the company of Yehudá ha-Leví, and Europe. He thus became a wandering wise man, well received for the knowledge he transmitted to the communities he visited: those of Beziers and Narbonne in France, Rome, England etc.

We are unaware whether he returned to Sepharad or whether he died in a European country. Howver, his multifaceted figure has left a deep mark on the whole intellectual life of the Jews of Europe. His biblical comments are some of the most highly appreciated in the Jewish world; his grammars are a common summary of the philological knowledge of Al-Andalus 11th century which it had not been possible to access up to then without knowing Arab and he introduced into the West the mathematical concepts of fractions and decimals.

He died in around 1167 according to some historians in Calahorra. His fame was so extensive that one of the craters on the moon, 42 kilometres in diameter, currently bears his name: Abenezrah.

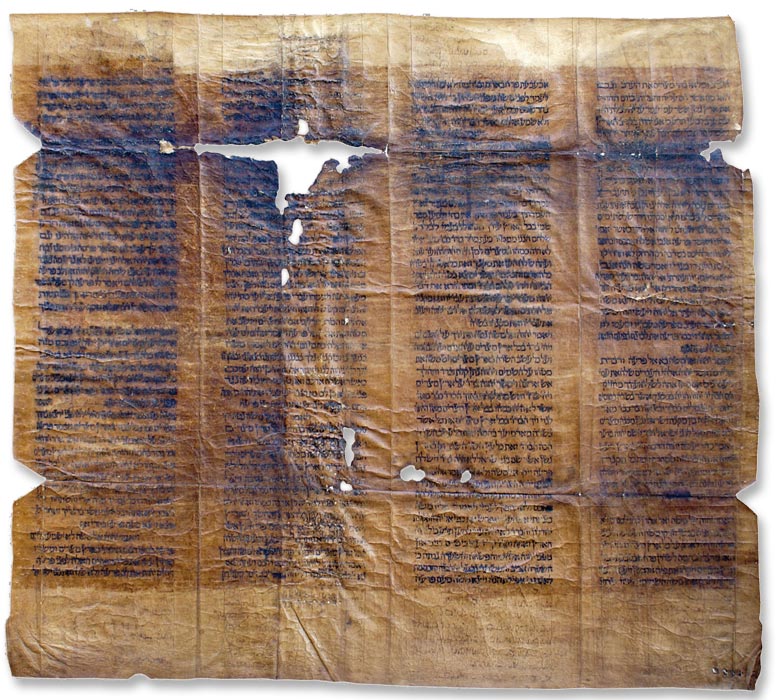

Sefer Torah of Calahorra

Amongst the scarce material remains of the Jewish past in Calahorra, pride of place must go to the fragments of a synagogueTorah which are kept in the Cathedral Archive and fragments of the book of Exodus, have been conserved, from Ex.IV, 18 to XI, 10.

The fragments of the Torahhave survived until today thanks to their use as the cover for two volumes of the Cathedral Chapterhouse Minutes, to be precise, for the volumes pertaining to the years 1451-1460 and 1470-1476.

These fragments belonged to a long scroll which contained the text of the Torahcomprising sections sewn to each other and going to make up horizontally very long strips which were rolled up at each of the ends on various wooden rods. To sew the sections together, tendons (orgiddim) were usually used, deriving from the rear hoof of a kosher animal or one which is fit for consumption by the Jews.

The written text is arranged into parallel columns and, as can be observed in the Calahorra fragments, great care is taken with the calligraphy and the ink is high quality. The length of the full manuscript would be around forty metres.

The fragments conserved from the Sefer Torah of Calahorra present a quadrangular shaped oblong and they constitute a piece of skin which is 1.49 metres long (one of the fragments is 81 centimetres and the other 68) by 63-64 centimetres wide. The text is distributed into nine columns of writing. The first five pages pertain to the worst conserved fragment (the one which bound the Minutes from 1470-1476) and the other four pertain to the part which is easier to read (and covered the minutes from 1451-1460). Each column of writing is formed by forty three lines as is the norm in the seforim and they are all equally spaced one centimetre between each other. The parchment which serves as the base is top quality, consisting of tanned skin, probably goat, written on 3 (in other words, by dint of its smooth cover), with very elegant square Hebrew writing which could be defined as a Sephardic Rabbinic scripture. The letters are slightly spaced between each other and the spaces are slightly bigger between words and between phrases. The ink used is very dark, carbon black.

The base parchment shows signs of having been reused and the remains of previous writing can still be observed, erased to reuse the material, which lends the manuscript even greater value.

The Torah (The Law)

This is the most important ceremonial object, recounting the story of the Jewish people. The Torah disseminates the Law and is written in archaic Hebrew of the first five Books of the Bible (the Pentateuch): Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy.

The scroll, formed by large segments of parchment sewn together, may reach a height of up to 80 cm. It is mounted on two wooden rods to roll it up, lift it and carry it. In the Ashkenazi custom the handles of these rods are generally covered by crowns or tips with some fine metal. The Torah is tied with a sash, simple or embroidered which is only untied when read out in public and it is protected by a case, generally embroidered. A breastplate, a reminder of the one worn by the High Priest, hangs from the handles on the case. In the Sephardi communities the Torah scroll is placed in a cylindrical box which is varnished and decorated and, generally speaking, wrapped in a sash. The majority of the boxes are wooden but there also silver and gold models. In turn, this box is kept inside the Ark.

The Torah scroll is treated with the greatest reverence although, self-evidently, it is not adored. It must not be allowed to fall nor must it be taken to an impure place. The parchment of the Torah scroll is not touched unless absolutely necessary. The reader avails of a wooden or silver pointer which has a hand with the forefinger extended.

Synagogues may have additional scrolls; the most common are the Song of Songs, Rut, Ecclesiastes and Esther which are read out publicly in the festivities of Passover, Shavuot(Pentecost), Sukkot and Purim, respectively.

The scroll most commonly found after the Torah is that of Esther which recounts the story of Purim. In view of the fact that it doesn´t mention the name of God, it is less holy than the other scrolls and can be found in many homes. It is kept in a box made of wood, silver or other materials.

Steps on the San Francisco slope

Leaving behind the cathedral and the Episcopal Palace, the steep slope of the cathedral leads to the steps of the San Francisco slope where the visit to the Jewish quarter begins, virtually going right through the wall which protected the Roman and Celtiberian citadel. A Jacobean shell recalls this point of connection between Calahorra and St-James' Way, further reinforced by the installation slightly further on of the hostel for pilgrims to the city. With its own enclosure within the walled city, the Jewish quarter must have had only one access gate (undoubtedly that at the confluence of Cabezo and Sastres streets), opposite the four main streets of the Roman city.

The Calahorra Jewish quarter

The Jews of Calahorra occupied the highest sector of the town which was situated in the vicinity of the castle and the Salvador church, today dedicated to San Francisco.

In the 14th century the Jews of Calahorra consolidated their location in this urban sector to such an extent that in 1336 they acquired form the chapterhouse by way of an exchange the space known as El Castellar or Villanueva, the Cantonera Tower and half of the Torre Mayor (Main Tower), all situated in the vicinity of the current Rasillo de San Francisco, extending as far as the Eras de Abajo wicket gate to the south of the town.

The Jewish quarter was totally surrounded by a wall in which at least one gate was opened as is stated in various documents from the 15th century in which reference is made to the so-called Jewish Quarter Gate which connected the Jewish quarter with the other of the city. Hence, in the exchange document dated 1336 the Jews were authorised to:

The Calahorra Jewish quarter thus constituted a true citadel within the city itself. It occupied the site of the former acropolis of Roman Calagurris and was located near the medieval castle. However, in the Lower Middle Ages this urban space had already lost its former strategic value for the defence of the city as narrated by Pero López de Ayala in the Chronic of Pedro I: in 1366 Enrique de Trastámara find it easy to gain access to Calahorra because this city:

Glossary

- jewish quarter: Traditional name given to the Jewish district or part of a city where the Jews´ homes were concentrated. In some cases it was determined by law as an exclusive place of residence of the members of this community. By extension, the term applies to any area known to be inhabited by families of Jewish culture.

- justice: institutions In the Kingdom of Aragon local justice institutions were at the head of the municipalities after the lord in the manor houses.

- mikveh, l. heb: Ritual bathing. Space where the purification baths prescribed by Judaism are taken.

- mudejar: Moslems who continued living in the territory reconquered by the Christians. They were allowed to keep practising the Islamic religion, use their language and maintain their customs.

- sefarad, l. heb: Name given by Jews to the Moslem and Christian kingdoms of the Iberian peninsula. Today it means Spain.

- torah, l. heb: Text of the first five books of the Bible.

- aljama, l. heb: Specific institution of the Medieval Hispanic kingdoms which dealt with the governance and internal administration of the Jewish community.

- circle: Discs which appear as a decoration, frequently coloured, in chapters of Jewish origin.

- converts converts: A christened Jew who has converted to Christianity.Jews converted to Christianity who returned to their place of origin after expulsion.

- kinot, l. heb: Elegy, dirge in verse read during the mourning of Tisha be-Av.

- kosher, l. heb: This means ‘suitable´ and it designates the set of dietary laws and standards on foodstuffs deemed to be pure and which could be eaten according to Jewish law.

- maravedis: Tax in force between the 13th and 18th centuries in the kingdoms of Valencia and Majorca by James I under the statute of April 14th 1266 and it consisted of payment of seven royal sueldos of Valencia (one maravedi) every seven years for each dwelling which had property valued at fifteen maravedis or more.

- merino: Administrative post existing in the Crowns of Castile and Aragón and in the kingdom of Navarra charged with sorting out conflicts in its territories, carrying out duties which are currently assigned to the judges. They dealt with the administration of royal property, harvests, land rental and levying and collecting fines. The merino mayor (oldest merino) is generally known by the name of the commandant.

- synagogue, l. gr: Gathering place for faithful Jews and the place of worship and studies. The term comes from the Greek synagogē which means place of congregation.

- wall-walk: Path around a city wall or parallel to it. In medieval Islamic cities it is the cul-de-sac which leads to private homes and which is closed at its entrance.