At Alfonso II el Casto square, following Eusebio González Abascal street as far as Porlier square, you have to stop to admire the proportions of the two beautiful Baroques which follow on the right: first of all, the Valdecarzana, then the Camposagrado, two gems which help to enrich the set of monuments in the square yet further.

The major transformations which have occurred over the centuries in the historic case of Oviedo have meant that today there are barely any material traces of the houses or streets in the former Jewish quarter of Oviedo, but they have not been able prevent the memory of the Jews who lived here for over centuries from remaining intact in the new city. This has undoubtedly been aided by the abundance of documents bearing testimony to the way those Jews from Oviedo lived, but also the will to incorporate this record into the common history of a city formed by the successive contribution of different cultures over the centuries. As regards the possibility of discovering a large part of the smooth and relaxed splendour of Oviedo through their Jewish references, the Asturian capital also contributes the original approach of combining the memory of the Jewish residents in the Middle Ages with the activity involved in a new synagogue, the Casina where, at present, around a hundred people are engaged in Jewish worship. Past and present thus intertwine and combine in one of the Spanish cities endowed with the most personality and with the greatest international projection, particularly through its world known Prince of Asturias awards.

The Jewish presence in Oviedo seems to already have been documented in the 11th century by a letter of donation to Legundia Gundemaris of a villa in Taranes owned by doña María who is referred to on repeated occasions as María, convert, by Didago Osoriz, the ombudsman, curate and executor of her mother´s will on June 18th 1046. The Jewish presence in the city in the 11th century is also referred to by the Council of Coyanza of 1050, held in Oviedo, which orders that:

Before this date numerous witnesses who seem to be Jews are mentioned n documents from the 9th and 10th centuries (Zabaiub iben Tebit, Sisebutus Iben Pepi, Theudericus Daneli, Aubaiub iben Thebiti, Abozehar, Abaiub, Hebregulfus, Theoda, Iosue, Salomon, Daniel, Iermias, Asur Falconis, inter alia). The Jews were thus involved in history which started in 761 when a group of monks set up its community on the hill of Oveto, giving rise to the city that Alfonso II would elect in 808 as the new capital of the kingdom of Asturias. In the 12th century when the Jewish community started taking shape in Oviedo, the Court had already moved to León though this did not prevent the latter from continuing to be prosperous with major commercial activity. Its increase was considerably aided by the construction of the first church of San Salvador and its consolidation as one of the main landmarks of the Way of St. James.

Historians situate the start of the period of maximum splendour of the Jewish quarter of Oviedo in the 13th century, coinciding with the unification of the kingdoms of Castile and León under Fernando III the Saint at a time when it seems that the Jews lived alongside the Christians at different points of the city (los judíos que se esparzían a morar por la villa, por que venía danno ala villa en muchas maneras que non queremos declarar). Between 1216 and 1225 the Jew Mari Xabe held the post of Merino of Oviedo, a high functionary in the royal administration with fiscal, judicial and military authority, but at the end of this same century the Ordinances of the Council of 1274 would start to put into place a series of restrictive measured which would considerably change the Jews´ status in society, starting a path which would not end until their expulsion in the 15th century.

In Asturias too the anti-Jewish directives were followed which were also applied in Castile, but they seem to have had less of an effect. The Council Ordinances regulated the lending business, forbidding its implementation at night except in cases of great need and when the recipient was a well-known resident of the city. The practice of pawning was limited, forbidding i ton stolen objects or objects from outside the city unless there were two witnesses attesting to the nature and origin of the pawned object. Loans to married women were forbidden without the consent of their husbands:

The ordinances also set up a specific district for Jews to live in, the district of Socastiello:

Hence, the new Jewish quarter, occupied from Puerta del Castillmaximo to the Socastiello New Gate. They could also live outside the walls should they so wish. It should be borne in mind that at that time the houses had already gone beyond the walled area and it is likely that some Jews had settled outside the walls as in the 15th century in the Western area there were still estates with the nickname de los judíos (of the Jews).

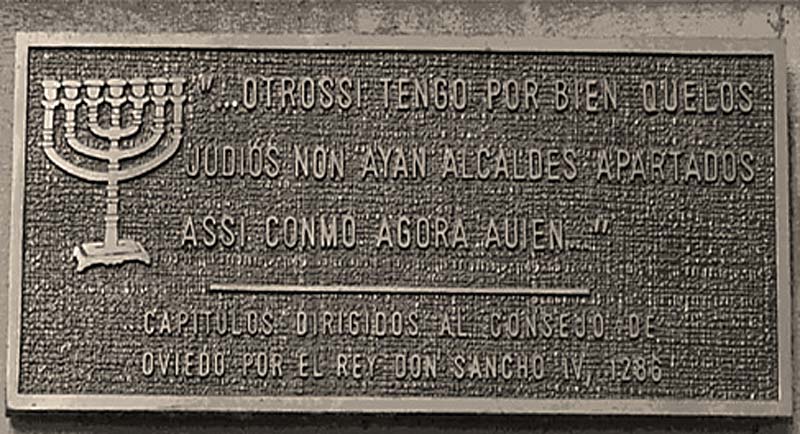

Twelve years later in 1286 Sancho IV laid down stipulations addressed to the Council of Oviedo in which the Jews were forbidden from having royal officials as they had had up to that juncture and they were subjected to the same officials as judged the cases of the other residents of the city. This is duly recalled on a plaque at Juan XXIII square:

A worse fate was to await the Jews of León in 1293 as in that year the King forbade them from owning arable land and imposed the obligation upon them to sew into their attire in a visible place the yellow emblem of their faith and race and they began to be pointed at by others.

In Oviedo during the bishopric of Gutierre de Toledo between 1377 and 1389, the restrictions on circulation and residence of the Jews of Oviedo increased or the existing ones were enforced more rigorously. Don Gutierre sentenced to excommunication anyone who objects to the Jews and Moslems from being expelled from the churches when divine acts are being celebrated, those who take part in their weddings or burials and any Christians who believe Jews or Moslems or undertake business with them, urging that no member of these two minorities to hold any public office. The bishop declares he is firmly against cohabitation between individuals of different religions whose members enjoy a friendly neighbourhood relationship, sharing the bitter and happy times of life: weddings, funerals, feasts and joyous events. This list of prohibitions makes it clear that cohabitation was rife and that the stipulations were not intended to solve a time of social conflictuality through the segregation of both communities.

Five letters of payment have been conserved from 1372 granted to the noble Don Gonzalo Bernaldo de Quiros by the Jew Don Abraham de Dios Ayuda, the main tax collector in Asturias. The witnesses were the Jew Don Abraham de Palencia, Don Yaco, Don Yusaf, a resident of Oviedo and another witness whose name does not seem Jewish but who is cited in the document as being Alvar García, a Castilian Jew. Acting as the tax collector we find Moses Falcón and Adam Giraldiz who intervened with others in letters of payment, agreements and settlements carried out in Asturias by dint of accounts and inquiries that Don Abraham El Barchilón rented from Sancho IV.

On March 31st 1492 the Monarchs signed the expulsion edict in Granada: within four months any Jews who failed to agree to be christened would have to leave their kingdoms. In 1499 the Royal Pragmatic of the Monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella is disseminated which stated as follows:

Until 1968 the derogation of the expulsion edict by the Catholic Monarchs was not recognised in Spain.

Alfonso II el Casto (the Chaste) square

Balesquida Chapel

Balesquida chapel, at the corner of the square with Eusebio González Abascal street, crowns the architectonic series of the Rúa with a Baroque building containing the image of the Our Lady of Hope and which constitutes a perpetual homage - as borne out by the scissors hanging from the corner balcony to the guild of tailors. the brotherhood of Balesquida was, in the 13th century, the beneficiary of the will of a lady from Oviedo, Velasquita Giráldez, and the feast day of this entity, Martes de Campo (Country Tuesday), is a local holiday in Oviedo.

Campoamor theatre

After passing through Carbayón square and admiring up close the grace of the figures on the Monument to the Concord (1997) by Esperanza dʼOrs from Madrid, we run into the Campoamor theatre.

A neoclassical 19th century building, the Campoamor theatre is not only an international icon referred to every year with the handing over of the Prince of Asturias awards, but also a non-stop cultural engine which keeps the Asturian capital busy all year long.

Cathedral

The extraordinary presence of the cathedral of Oviedo defines the profile of Alfonso II the Chaste square, the most central one in the city, located right on the heart of the medieval city. Endowed with flamboyant Gothic style, the San Salvador cathedral started to be erected in the 14th century on the site of the previous church of the same name at the behest of Bishop don Gutierre, a champion of the fight against the Jews, though the set was not completed until the 16th century.

In addition to its architecture, the cathedral of Oviedo stands out for the numerous jewels it holds in its interior such as the Holy Chamber, declared by Unesco in 1998 as Heritage of Humanity, where the relics donated to the cathedral by Alfonso II the Chaste are kept; the Lignum Cricis, or Victory Cross, a symbol of the Principality of Asturias. Wamba, the bell which can be heard every day at the top of the belltower, is said to be the oldest cathedral bell in Spain.

In addition to its status as an episcopal seat, the cathedral of Oviedo also served as the Royal pantheon of the kingdoms of Asturias and León. The Kings and Queens of Asturias buried here include: Fruela I, Bermudo I the Deacon, Alfonso II the Chaste, Ramiro I, Ordoño I and Alfonso III the Chaste; those of the Crown of León include García I, Elvira (the wife of Ordoño II), Fruela II, Urraca of Navarre (the wife of Ramiro II) and Teresa, the wife of Sancho I the Fat.

The exhortations of Don Gutierre de Toledo

In the 14th century, a century in which several synagogues in the diocese were seized, the Bishop of Oviedo don Gutierre de Toledo was characterised by the strictness of his homilies and sermons against Moslems and Jews in which he even threatened the excommunication of anyone who had any kind of dealings with them, even commercial, and asking for the members of these two communities to be banned from taking any public office. In actual fact, all he achieved was to reject a popular practice of totally peaceful cohabitation which had spread throughout Oviedo society.

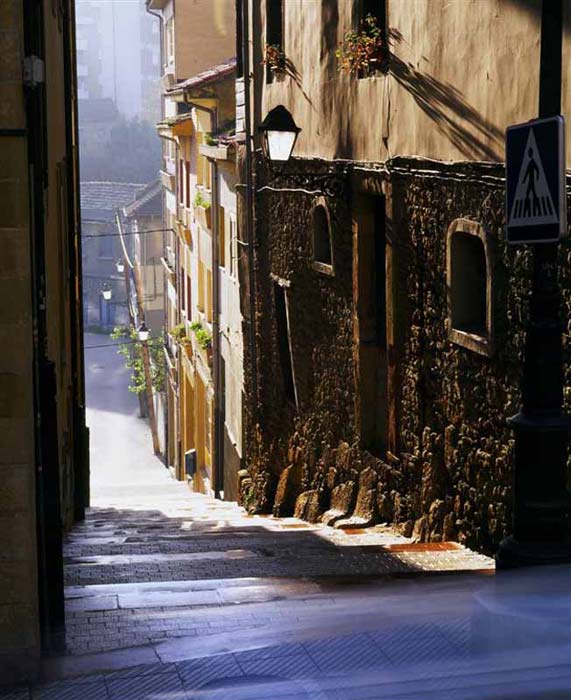

Cimadevilla Street-Rúa Street

Cimadevilla and Rúa streets form one of the main thoroughfares which crossed the walled city and led from its main access to the Jewish quarter. At Rúa street you will find the house of Oviedo-Portal which forms part, along with the adjoining house of Solís-Carvajal and the Velarde palace, of the Museum of Fine Arts of Oviedo (currently undergoing expansion and remodelling) whose rich heritage with over eight thousand pieces catalogued have made it one of the most important of its kind in Spain; the house was erected in 1660 in line with the project by the architect Melchor de Velasco to serve as the home of the alderman of the city don Fernando de Oviedo-Portal.

Constitution square

From Fontán, Fierro street, where the church of St. Isidore is located, leads to Constitución square, a broad space dominated by the colonnades of the town hall whose central arch coincides with the old access gate to the walled city.

The Torre del Reloj (Clock Tower) is one of the references of this building endowed with good proportions, dated as being from the 17th century, serving as a time tunnel to leap, once again, from the Baroque to the Middle Ages, in an environment which draws us a little closer to that of the historic Jewish quarter of Oviedo.

El Fontán

Travelling through time from the years of the Inquisition and the persecution of Judaizers which coincide with the foundation of the university of Oviedo, the route to Fontán street - where the current La Casina synagogue is located – starts on Ramón y Cajal street whose initial stretch as far as Riego square coincides, on the left, with the layout of the former medieval defensive wall.

Still outside the walls, and after leaving behind us in the square the beautiful Bernaldo Quirós palace, Los Pozos street intertwines with Rosal street which opens out, also on the left, into Fontán street. The Zapatos arch symbolically marks the entrance to Fontán street and square, the closed market and street market which is open every day; a space for popular architecture and for the merry cider bars which splash the ground with fermented apple juice... The stone columns mark the modern character of this everlasting market where the sculptoric reference of the traditional pottery dish sellers is not lacking. Vamos al Fontán (Let´s go to Fontán) is the phrase which defines the fondness of the Oviedo residents for this space awash with colour where number 11 of this street houses the contemporary synagogue.

Former Castiello Gate

The palace of the Count of Torreno, on the opposite side of Eusebio González Abascal street, overlooks Porlier square, at whose western end the Castiello gate used to be located, in other words, one of the castle gates located here and which served to access the city inside the walls and the Jewish district.

Former Socastiello Gate

Annexed to Porlier square, Juan XXIII square marks another of the limits of the Jewish quarter. More at less at the place where the square meets the start of Jovellanos street must have been the Socastiello gate or Nova gate referred to in the Ordinances of 1274.

Jewish butcher´s. Plaza de Trascorrales

No sooner do we pass the threshold into the old city, than we meet Huevos alleys which leads to Trascorrales square where, in addition to the monument to the Lechera asturiana (Asturian Dairy), there is the building of the former Fishmonger´s which some researchers relate to the Jews and some nearby butcher´s where the Jewish community would get their Koshermeat.

The butcher´s

The meat eaten by the Jews had to be slaughtered according to a very strict religious ritual. This was carried out at the slaughterhouse and the meat was sold at the butcher´s.

The slaughterhouse, market or scaffold was a space which acquired a certain ritual nature by dint of the liturgy ( shejitah ) undertaken there whilst slaughtering animals whose meat was intended for human consumption (kosherfood). The norm was for the slaughterhouse to be located in an area on the outskirts of the Jewish quarter to avoid unpleasant odours in the city.

The meat was sold at the butcher´s where sales points were erected which were let out. The income obtained was used for certain needs of the aljama.

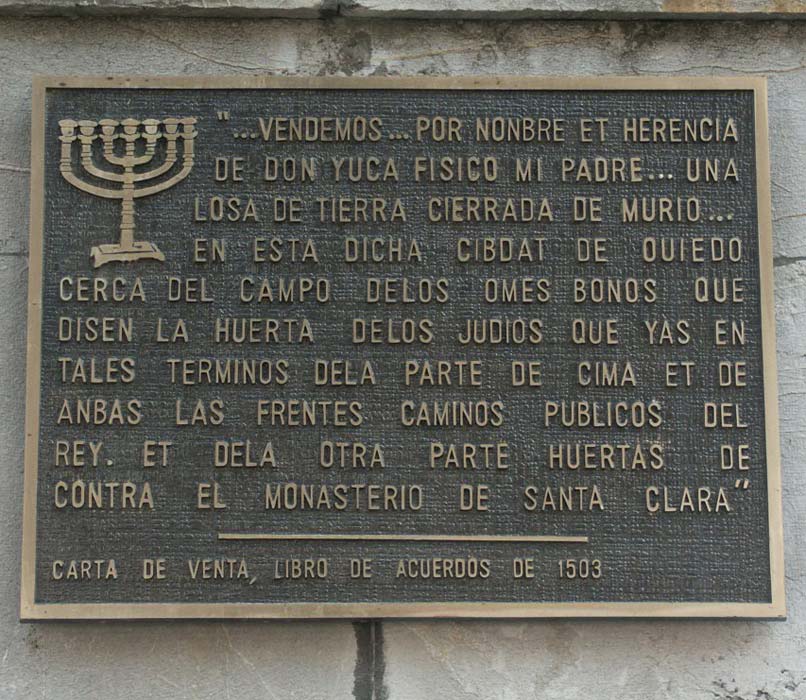

Jewish cemetery

According to the purchase and sale document of 1412, the cemetery of the Jewish community of Oviedo was situated at a plot near St. Clare´s convent, outside the walls of the city, located more or less where the Campoamor Theatre is currently to be found. The purchase and sale document for the land, owned by Mencía Fernández, the daughter of the doctor Yuçaf, and her husband Pedro Fernández Carrio, states that this plot was called la huerta de los judíos (the Jews´ garden).

A subsequent document dated 1530 confirms that this plot from 1412 was the Jewish cemetery. After the expulsion decreed by the Catholic Monarchs, the Council seized the cemetery, but left it in a state of abandonment which was taken advantage of by some residents to enter and farm the land and the Council bestowed them these rights. In the dispute the residents declared that the plot had been a tomb for the Jews and that they had seen many monuments and tombs there. One of the witnesses, Juan González de Lampajúa, was mentioned who told of a conversation with someone called Solomon, a Jew, who had said to him that the garden was a tomb for the Jews who lived in the city and that their forefathers were buried there. Another witness, Juan de la Podada, confirmed he had heard that the garden had always been a tomb for Jews and that he had seen there six or seven monuments and Pedro Menéndez del Estanco stated the same.

Entre el cementerio y la judería debió de haber, como mandan los cánones hebreos, una corriente de agua que separara el mundo de los vivios del de los muertos; hoy seguramente discurre de manera subterránea.

Between the cemetery and the Jewish quarter there must have been, as the Hebrew canons order, a stream of water separating the world of the living from that of the dead; today it probably runs underground.

The cemetery

The cemetery was located outside the walls at a certain distance from the Jewish district. The chosen site:

- Must be on virgin soil

- Must be on a slope

- Be oriented towards Jerusalem

The Jewish quarter had to have a direct access to the cemetery to prevent the burials from having to pass through the interior of the city.

After 1492 the monarchs authorised (in Barcelona in 1391) the reuse of stones from Jewish cemeteriesas construction material. It is thus not unusual to find fragments of Hebrew inscriptions in several subsequent constructions.

Despite the pillaging they suffered from the late 14th century, the memory of these cemeteries has remained in the name in certain places, for instance, Montjuïc in Barcelona or Girona. We are aware of the existence of more than twenty medieval Jewish cemeteries. Others are only known of thanks to the documentation or the headstones conserved. The one in Barcelona at Montjuïc was excavated in 1945 and 2000, the one in Seville in 2004, the one in Toledo in 2009 and the one in Ávila in 2012.

La Casina Synagogue

In 1999 Oviedo City Council granted the building known as «La Casina» at number 11 of Fontán street to the Jewish community, Principality of Asturias. In addition to a synagogue, a Jewish cultural centre has been set up in this building dedicated to studying, disseminating and promoting the Jewish culture such as the Jewish Book Fair or acts with schoolchildren to remember the holocaust. They also collaborate with the Zibia Lubetkin group to educate about the memory of the Shoah.

La Casina

Opened in 1999, the Oviedo synagogue, better known as La Casina, currently serves over a hundred people and as well as serving as a prayer room, constitutes an active cultural centre with various activities all the year round. The Torahscrolls, the menorah, an up-to-date mezuzah or Rabbis´ chair lend a truly Hebrew touch in the midst of a district dominated by colour and hustle and bustle and presided over by a splendid porticoed square, rehabilitated very recently not without some controversy amongst the residents.

La Foncalada

Malleza or Toreno Palace

Monolith in homage to the victims of the Shoah

In 2005 Oviedo city council, at the behest of the Israeli Community of the Principality of Asturias, inaugurated a Monolith in homage to the victims of the Nazi holocaust. The Monolith, situated at Parque de Invierno, near the bread basket, is a place commemorating a historic occurrence which should never be forgotten.

Oviedo University

The stern look on the face of Fernando de Valdés Salas in the statue representing him at the center of the cloister of Oviedo University, undoubtedly incarnates the pompous character of the founder of this institution, but it is also, if you want to look at it that way, a certain examination of conscience after his work as the grand inquisitor between 1547 and 1566 when he was the central figure, amongst other cases, in the famous proceedings against Bartolomé de Carranza, the author of a big Índice de libros prohibidos (List of Prohibited books), but also an unflagging driving force behind cultural and charitable ventures; perhaps today don Fernando would not have been surprised to know that the volumes kept at the University library include two magnificent editions of the Ferrara Bible from 1553, a Bible in Spanish translated word for word from the Hebrew truth by most excellent academics and seen and examined by the office of the Inquisition.

Design in 1574 by Rodrigo Gil de Hontañón, the building, surrounded by the mandatory university quarry which established the higher jurisdiction of the chancellor, accommodated the faculties of Arts, Canons, Laws and Theology after its solemn inauguration in 1608 which its main promoter Valdés was unable to attend as he died a few years previously. The magnificent building which can be seen today is the culmination of profound restoration after the damage caused to the property during the October Revolution of 1934 and the subsequent Civil War.

Palace of the Marquesses of Camposagrado

Plaque at Campoamor theatre

It must have been via this Socastiello gate, or via the other of Castiello, that the Jews of Oviedo in the Middle Ages came out to bury their dead in the fossar (graveyard) or cemetery which stood in the place currently accommodating the Campoamor theatre. On one of the theatre walls which give out onto 19 de julio street, the following part of the document recalling the purchase and sale is reproduced on a plaque:

Plaque at Juan XXIII square

At Juan XXIII square, where there is little to remind us of the traditional labyrinth of Separdi Jewish districts, a plaque, placed on the pharmacy wall, recalls a fragment of the chapters of King Sancho IV addressed to the Council of Oviedo in 1286:

Porlier square

At the same Porlier square, the sculpture by Eduardo Úrculo El regreso de Williams Arrensberg (The return of Williams Arrensberg - 1993),a lifesize portrayal of a traveller with a hat and overcoat, resting on his suitcases, has become a true symbol of the city de Oviedo.

On the northwestern side of the square an explanatory Jewish settlements´ plan situates in this square the main Jewish landmarks of Oviedo, at least since the period when the members of the aljama ceased to be free to elect their place of residence in the city to focus on a specific place as from the Ordinances of the Council of Oviedo of 1274.

The space occupied by this square, plus that part of the block formed by the building on the northern side and that of the current Juan XXIII square, constitutes the essence of the Jewish quarter of Oviedo from the Castillo gate to the Socastiello Nueva gate and from the gate outwards, should they so wish. Those who drafted the Ordinances justify these limitations by the fact that the Jews»se esparzían a morar por la villa, por que venja danno ala villa, en muchas maneras que non queremos declarer», but they use this opportunity to establish a series of impediments to their activities. From this point onwards the Jews of Oviedo can no longer accept the pawning of stolen objects, grant loans to women without the autorisation of their husbands or carry out financial activities after nightfall.

Rúa Palace

At the confluencia of Rúa street with Alfonso II el Casto square lies the house or palace of Rúa, from the 15th century, also known as the palace of Marqués de Santa Cruz del Marcenado and regarded as the oldest civil building in the city.

Its solidity contrasts with Llanes House which stands by its side and which is dated 1740 as the residence of the Knight of the Order of St. James Menendo de Llanes-Campomanes. Opposite both constructions the statute La Regenta (wife of the Regent) displays its melancholy, a work by Mauro Álvarez from 1997, one of the numerous works of art occupying the city where the presence of the sculpture in the street has become one of its most genuine distinguishing features.

The Jewish quarter of Oviedo

After the Ordinances of the Council in 1274, the Jews of Oviedo were required to live in the Socastiello district, alongside the Citadel and the city walls. The Jewish quarter of Oviedo occupied the area from Castillo Gate to the Socastiello New Gate. They could also live outside the walls should they so wish. It should be borne in mind that at that time the houses had already gone beyond the walled area and it is likely that some Jews had settled outside the walls as in the 15th century in the Western area there were still estates with the nickname de los judíos (of the Jews).

The Royal Castle and the Citadel in the 13th century occupied more or less the place where today the Telefónica building is located, alongside Porlier square, the Castillo Gate was on the left of the latter and the Nueva gate of Socastiello could have been either near the former San Juan street or the end of Cimadevilla street, as both gates are called Puerta Nueva (New Gate) in documents from the time. The internal limits of the Jewish quarter inside the city are harder to define.

No material remains of this Jewish quarter have been conserved. Neither have the same, narrow streets shared by Christians and Jews in the old Oviedo for centuries and the historic documentation which enables us to reconstruct and imagine the inhabitants of said Jewish community: Bartolomé Guion, notary; Beneito, moneychanger; Adan Giraldiz, Pedro Giraldiz, moneychangers; Petro Giraldiz, weaver; Petro Michaeliz, furrier; Aben Arsar, Asur Falconis, Bartolomé Alfageme, Don Symon, Annaias Tanoz and many more.

Valdecarzana Palace

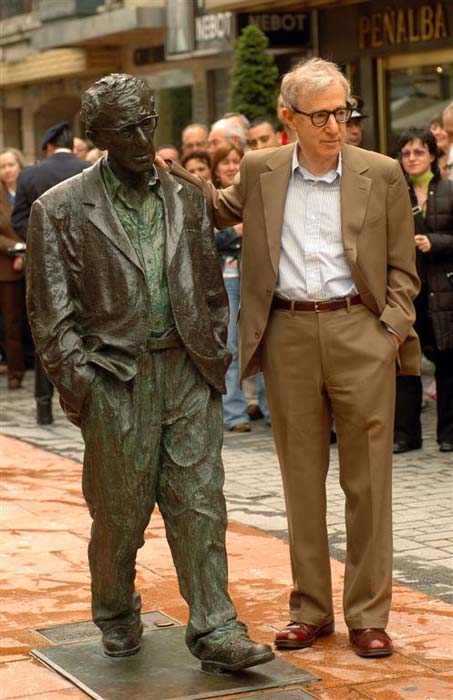

Woody Allen Statue

Following the tracks too of one of the most well-known Jews of our time, in Milicias Nacionales Street, opposite San Francisco park and slightly set back from the traffic on Uría street, stands the statue of the film-maker Woody Allen, a work by Antarúa from 2003, walks absent-minded as if pondering the long history of the Jews of Oviedo in the old district from where its steps appear to come... A final contemporary homage to the memory of a collective which formed part of the history of the city for a large part of the Middle Ages.

Glossary

- jewish quarter: Traditional name given to the Jewish district or part of a city where the Jews´ homes were concentrated. In some cases it was determined by law as an exclusive place of residence of the members of this community. By extension, the term applies to any area known to be inhabited by families of Jewish culture.

- kosher, l. heb: This means ‘suitable´ and it designates the set of dietary laws and standards on foodstuffs deemed to be pure and which could be eaten according to Jewish law.

- merino: Administrative post existing in the Crowns of Castile and Aragón and in the kingdom of Navarra charged with sorting out conflicts in its territories, carrying out duties which are currently assigned to the judges. They dealt with the administration of royal property, harvests, land rental and levying and collecting fines. The merino mayor (oldest merino) is generally known by the name of the commandant.

- shoah, l. heb: Lit. Massacre. Extermination of the European Jews during the 2nd World War.

- aljama, l. heb: Specific institution of the Medieval Hispanic kingdoms which dealt with the governance and internal administration of the Jewish community.

- synagogue, l. gr: Gathering place for faithful Jews and the place of worship and studies. The term comes from the Greek synagogē which means place of congregation.