Remains of the former Jewish fence are still conserved under the tower of the current Cava Palace, restored in the 19th century, which could correspond, according to various studies, to the wall-walks of Abzaradiel which were said to have stretched from Santo Tomé to the Judíos Gate. At the latter were the gates of the largest suburb of the Jews (a suburb which may have encompassed the entire Jewish quarter with the exception of Alacava and San Román) and also the wall-walks of Assuica. This may have formed the first fence cutting off the Jewish quarter from the rest of the city before its upper extension to Alacava and San Román.

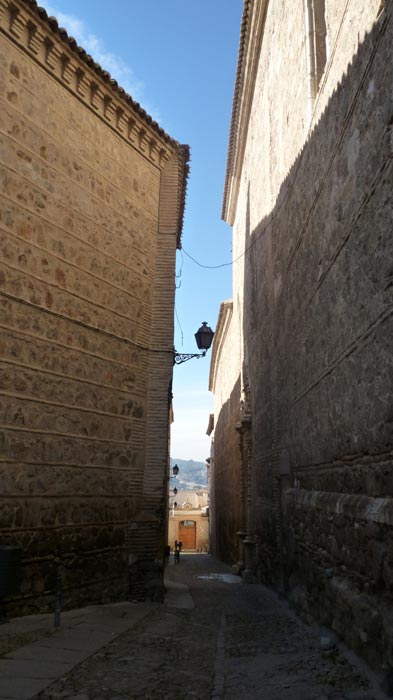

Rightly regarded as a true «city within a city», the madinat al-Yahud, or city of the Jews, constitutes a broad urban space which occupies almost ten per cent of walled Toledo. Divided, in turn, into different districts which correspond to the different stages of its expansion, the Jewish quarter of Toledo is an intricate maze which needs to be marked out in order to gain a real overview of what the Jews of Toledo were like and how they lived for at least eleven centuries.

Although the oldest written documents date their presence back to the 4th century, in the context of the Roman Toletum, the Sephardi goes further back and relates the Jews to the very mythical origin of the city, deeming it likely that the first Jews arrive in the Iberian Península at the time of the Assyrian and Babylonian exiles in the 8th to 6th centuries B.C.

Historically speaking, there is sufficient evidence of the Jewish presence as from the approval of anti-Jewish measures or the confirmation of the previous ones carried out at the different councils held in the city. Under the Visigoth monarchy (5th to 8th centuries), the period when Toledo was the capital of the kingdom, the Jews formed a numerous colony and hence the existence of a Jewish quarter can be assumed from at least the 6th century.

As from the Third Council of Toledo, (589) when King Recaredo and his Goth subjects abandoned Ayrianism to convert to Roman Catholicism, there began to be problems with cohabitation. The persecutions and punishments which started upon the conversion of Recaredo led to many Jews deciding to convert to Christianity, leave or stay and resign to the new situation.

The hostile legal stipulations vis-à-vis the Jews of Toledo continued until the occupation of the city in 711 by Moslem troops. The destruction of Visigoth power at the Battle of Guadalete in 711, the ignorance of the Arab combat method and the probable death of Rodrigo at the battle left the door open to the leader Táriq ibn Ziyad to take control of Toledo in 711. Faced with repression, the Jews greeted the Arab invaders with open arms as their saviours after the fall of the Visigoth regime. What is for sure is that the city, unprotected as Rodrigo took his comitatus with him and the swordsmen of the royal guard, did not put up a fight so it would not be unusual to assume that the Jewish community had opened the gates in the wall to the Moslem troops whilst the inhabitants of Toledo were at mass. Legend or otherwise, the fact of the matter is that the Arab domination of Toledo began a long period for prosperity for the Jewish community.

The Moslems, as they regarded Jews as «people of the Book»too, afforded them great freedom. The Jews soon assimilated the uses of the new governors, adopting their language as a cultural vehicle and they used it until the 13th century, even in their internal or religious documentation. During this time until the late 11th century, many learned Jews were born or educated in Toledo such as Abraham ibn Ezrá or Yehuda Ha-Levi himself. It was here that Abraham ibn al-Fakhar was born and wrote his poetic works, dying in 1231, Israel of Toledo and many more who displayed the light of their knowledge in the Castilian court.

In around 1000 the Jewish community of Toledo was insignificant and prior to this date there is scant data about its presence. They are families who cohabit with the Christian population, doing business and working in the fields. Their fate was tied to that of the Reconquest whose ebbing and flowing directly impacted the state of things. Moslem Spain afforded great opportunities a high standard of living. The Jews of Al-Ándalus took advantage of the tolerant climate of the Caliphate and took the values of that refined civilization as their own without giving up their religious beliefs.

In 1085 Alfonso VI conquered Toledo and the Jewish quarter began am age of prosperity and population growth. The Jews helped the Castilian King conquer the city and Alfonso VI granted them the same rights as the Christians. The height of the Jewish community was maintained with the Christian Kings, accruing their social and political representativeness and becoming the most important Jewish community in the Crown of Castile in the 12th century. The doctor and nasi of Toledo Joseph ben Ferruziel, also known as Cidellus, was to become the monarch´s prime minister and this gave way to a series of Jews holding important office in the court of Castile.

Despite royal protection, Isaac ben Jacob na-Cohen, known as Alfassi, an 11th century Talmudist, refers to persecutions in Toledo in 1090, five years after the entry of Alfonso VI in Toledo. In his Responsa, Alfassi alos talks about the slaughter of Jews in 1108, the year in which Salomón ibn Farissol died. Neither does it seem that the equality between Christians and Jews would last for long. A decree of 1118 forbade the Jews from having any jurisdiction over a Christian, leading us surmise that this was previously habitual.

In 1135, with the arrival of the Almohads to Al-Ándalus, there was a headling rush of the Jewish population feeling to Castile and Aragón, leaving Moslem Spain virtually free of Jews. The Almohads, «those who recognise the unity of God», or Banu Abd al-Mumin, was a Moslem dynasty of Berber origin which emerged in modern-day Morocco in the 12th century as a reaction to the relaxed religious attitudes of the Almoravides and they dominated the north of Africa and the south of the Iberian Peninsula from 1147 to 1269. Faced by Almohad intransigence, the aljamas, such as that of Toledo, increased their population with Jews from Moslem Spain. May arrived in 1147 and the nasí of the Jews of Toledo was Judá ben Joseph ibn Ezrá, a relative of the poet.

The consequences of this mass emigration proved decisive. Toledo was settled by poets, grammaticians, philosophers, scientists, doctors and other learned men, making the city their main destination. The Archbishop of Toledo don Raimundo de Sauvetat, who later became the Chancellor of Castile with Alfonso VII, wished to take advantage of the climate which allowed Christians, Moslems and Jews to live in harmony, provided his backing to different translation projects requested by all the courts of Christian Europe. The prestige of the School of Translators of Toledo was so great that not even the anti-Jewish stipulations of the Lateran Council in 1215 could stop it from flourishing.

Royal favouritism to the Jews was frequently the cause of unrest such as the revolt of 1178 in which the Jewish lover of King Alfonso VIII died. This revolt also put paid to Judá and Samuel Alnaqua. Or the revolt of 1212, coinciding with the arrival of Jews fleeing French intolerance. The Archbishop of Toledo responded by burdening the Jewish community with new taxes: any Jews aged over twenty would have to pay an annual encumbrance, whilst they would have to pay an additional charge for profits foregone when purchasing houses from Christian owners.

The reign of Alfonso X the Wise was the one which entailed the greatest prosperity and splendour for the Jewish community of Toledo. Their situation is attested to by the amount of taxes the aljama paid in 1284: one million maravedis. During his reign the Jewish quarter of Toledo became known for its scale, the luxuriousness and beauty of its public buildings and the intellectual quality of its rabbis.

After the death of the Wise king, the Jews fell into disrepute again. During the 14th century, the epidemic of the Black Death in 1348 and the war between Pedro I the Cruel and Enrique of Trastámara resulted in deep social ill-feeling borne out by the attacks on the Jewish quarter in 1355 and 1391. In addition, there was a fire in the enclosure of Alcaná, a commercial district where the Jews had their shops, workshops and some houses. Until 1222 the year in which the cathedral began to be expanded, the main mosque, consecrated in December 1086 to Christian worship, remained relatively unchanged. In the late 14th century the construction of the cloister was planned and this began to be built on August 14th 1389. There is some doubt as to whether the fire was started by the Chapterhouse of the cathedral to allow the construction of the cloister planned by Archbishop Pedro Tenorio in the Alcaná area.

The anti-Jewish revolts of 1391 reached Toledo too. On June 18th the Jewish quarter of Toledo was attacked at night in a similar way to other cities in the kingdom. The victims of the slaughter included prominent craftsmen, poets and men of letters. The majority of the synagogues of the city we destroyed or seriously damaged. In February 1398 the King ordered the mayor Juan Alfonso and the main treasurer Juan Rodríguez de Villareal who carried out investigations into who had committed the robberies in the Jewish quarter of Toledo, imposing a fine of thirty thousand gold doubloons on the guilty parties.

The disastrous economic consequences for the city were soon felt; particularly by private individuals, monasteries and other religious institutions who lost the income they had from the taxes on the Jewish aljamas. The hardest hit was the chaplains whose ecclesiastical profits derived from the rents in the Jewish quarter.

In 1411 the Dominican Vincent Ferrer arrived in Toledo on his preaching campaign of 1411-1412 and according to Francisco de Pisa in his Descripción de la Imperial Ciudad de Toledo (Description of the Imperial City of Toledo) of 1605:

Doubt was later cast on this testimony by Francisco de Pisa as it seems that Vincent Ferrer gave his sermon outside the walls (as the Cathedral could not accommodate everyone who wished to hear it), but it is clear sign of the state of affairs as regards the Jewish community of Toledo.

The aggressiveness of the Christians to Jews and Moslems, which became ever more pronounced, resulted in the proclamation of a series of ordinances against them in 1451 whereby they were required to obey a series of restrictive measures such as the prohibition to walk around the streets at night, enter churches or monasteries without authorisation, leave their houses during Christian festivities as well as the obligation to wear distinctive signs sewn into their clothes. The Jews of Toledo had already complained that in 1450 King Juan II had ordered the revocation and cancellation of all anti-Jewish ordinances in place in the Castilian kingdom as there had been many places where they had done so and the Jews had left. The King ordered the Town hall of Toledo to follow his order and the latter, meeting on February 23rd 1452, reviewed the ordinances, doing away with some, but modifying and maintaining others.

Several fires accompanied the conditions of social disequilibrium which were still in place in the 15th century. Supported by the League of Nobles, who symbolically dethroned Enrique IV in the so-called Farce of Ávila on July 5th 1465 and crowned his brother Alfonso (recalled by Jorge Manrique in Coplas por la muerte de su padre (Coplas on the death of his father) in 1476), the old Christians started clearing the lands of Castile of all those who had Jewish blood, whether they were Jewish or convertsas well as Moslems converted to Christianity. The latter, feeling threatened, staged an uprising in Toledo on the day of the fires of Magdalena, on July 22nd 1467. Heavily armed, the converts surrounded the cathedral and they kept the Christians under siege after killing two canons and a few others. A thousand Christians and reinforcements of one hundred and fifty men arriving from Ajofrín came to the rescue of those besieged. The converts took gates and bridges of the city and put up four barricades. The fighting then began on the outskirts of the cathedral and continued in the Magdalena district. Those besieged were able to get out, some say via the door giving out onto Ollas street; other via the gate door onto Reloj street. The converts responded by setting fire to the Magdalena district. All the houses neighbouring the Don Diego Yard burned to the ground immediately. Friar Mesa, a chronicler of Castile, says that the fire spread quickly because of the wind to Trinidad, passing near San Juan de la Leche, reducing Nueva and Sal street to ashes, reaching as far as the spices market and the church of Santa Justa. According to the chronicler the fire continued via Tintes street and burned down the house of Diego García de Toledo. One thousand six hundred houses were destroyed. The old Christians, after many days of fighting, were finally able to control the fire and reduce the converts. Their ringleader, Fernando de la Torre, was put to death; the same fate would befall many other converts in the following days.

The uprising was of little benefit to the insurgents who were forced to flee from Castile with their assets. Those who decided to stay, deprived of their right to bear arms or hold posts in the Administration, finally had to convert and attest to their good faith to be Christians before the Inquisition Court.

After the Edict of expulsion by the Catholic Monarchs, on March 31st 1492 the aljama of Toledo disappeared and the public buildings of the Jews, save the odd exception, were distributed by the Catholic Monarchs between the nobles and religious orders to make up for the loss in income. Many inhabitants of the Jewish quarter decided to convert, but others left, en route to exile. There are various details attesting to the devotion they had to this land which was theirs too. They retained their Judaeo-Spanish in their destinations and more importantly, they kept the keys to their homes thinking they might come back.

They never did.

Abzaradiel Wall-walks

Alacava District

Al-Aqaba or Alacava, the district annexed to the main Jewish quarter or largest suburb of the Jews, densely populated and popular. The Alacava district is annexed to the largest suburb of the Jews after which the latter extends to Santo Tomé and is progressively isolated from the Jewish quarter after 1355 when it was sacked by the troops of Enrique of Trastamara .

At San Antonio square, for centuries a market and meeting place between Jews and Christians, Hospedería de San Bernardo street appears in a Northwesterly direction, which was the main thoroughfare of the Alacava district or Al-Aqaba at a time when the Jewish quarter was expanding outside its traditional limits.

Arquillo del Judío (Small Arc of the Jew)

Very near the confluence of Reyes Católicos and Ángel streets where the Sofersynagogue was situated (scribe), probably dated between the late 12th century and the early 13th (though solely documented as from the 14th century), is also the site of what is known as the Arquillo del Judío (small arch of the Jew), a passage which joined the districts of Assuica and Alacava, or Al-aqaba with the main Jewish quarter via the Travesía del Arquillo and which is said to have borne witness to the sale of the jewels of Queen Isabel the Catholic to finance Colombus´ American venture.

The small arch we can see today is not the original one.

Arriaza district/street

The Arriaza district must have existed since well before the last decade of the 13th century. The first documentary evidence of the district is from 1292 when the monastery of San Clemente buys three houses –almazría, a cellar and six shops – situated together in the Suburb of the Jews on del barrio Arriaza street in the city of Toledo. Under the third house, the furthest down, forming a corner, there were six shops. Three gave out onto the square where the butcher´s shops are situated and the other three were opposite the shops which leaned against the castle wall on the street of the bailiff and tax collector Abuibrahim. The three houses would still be owned by the monastery until the second half of the 18th century.

A century after the expulsion of Jews and Moslems, the name of Arriaza was no longer used and was replaced by that of Barrio Nuevo (New District) which designates the whole of the Jewish quarter to the south of Santo Tomé. According to Jean Passini, the Arriaza district included at least the barrio de Arriaza street; another street, packed with commercial activity, perpendicular to the latter; and behind the three houses described above, the Carniceros (butchers) square. The district ended at the Castillo Viejo (Old Castle) which it may have skirted but did not incorporate.

Assuica District

The Assuicadistrict (diminutive of souk, market, in Arab) was located in the Ángel street area which owes its name to the Gothic angel of the house where the Cuesta de Bisbis comes out and it was the former main street of the Jewish quarter, connecting the Assuica district with those of Alacava and Santo Tomé.

The arch which joins both sides of the street is one of the distinguishing features of this route, teeming with historic content which merges with Reyes Católicos street, forming a district round about, that of Assuica, which brings together some of the major references of the Jewish quarter such as Juderia street, Barrio Nuevo square or the Santa María la Blanca synagogue.

Baba Alfarach District

From the Barrio Nuevo square, and via the Cuesta de Santa Ana the vantage point of Roca Tarpeya is reached, a mythical space in Toledo from where, it is said, the Romans would throw those sentenced to their deaths, following an ancestral custom.

Around Roca Tarpeya, where today the Victorio Macho Museum was erected, there was also a small Jewish core, called the Bab Alfarach District where the Gate of Alfarach or Consolación was located in an environment with some enviable views over the Tagus and the country houses on the other side of the river.

Barrionuevo square (Jewish market square)

Caleros District

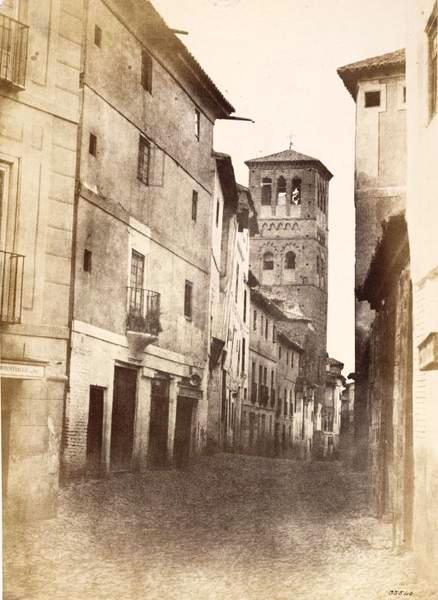

After going through, via the streets of San Clemente and San Pedro Mártir, the upper suburb, Gordo alley connects with Valdecaleros square which constitutes a small core around which the Caleros district was organized where one of the ten famous synagogues of the city was situated which are mentioned in a well-known medieval poem. After passing through Aljibillo and Rojas streets, the route stops at Salvador square, the main access to the Jewish quarter via the east. Here the splendid church of El Salvador, built on the site of a former mosque, gives us a short history lesson, conserving built into its tower Roman and Visigoth elements and Moslem horseshoe arches supported on Gothic chapters in the interior.

Caleros synagogue

Caleros synagogue is first mentioned in a document dated 1355. Having disappeared very suddenly, the synagogue site is conserved at Marrón square which has existed since the 15th century.

It is likely that just like the other synagogues of Toledo, the Caleros synagogue suffered the effects of the anti-Jewish movement of 1391. Abandoned in the late 14th century or slightly later, it was not mentioned again until 1418. In 1448 the synagogue is a house owned by the Archdeacon of Niebla who, since 1434, gradually acquired houses in this district for his assets, a quarter of which was bought by Juan de Silva, the Count of Cifuentes in 1460.

The main house of the Count of Cifuentes, called «de los sennores Reyes» in the second half of the 15th century where the monarchs would be lodged in the second half of said century and even during the following century, took up a large block in the area where Caleros lean-to is situated. On the other side of the lean-to at the corner of Caleros street with the lean-to of San Pedro Mártir was the «accessory» house, deriving from the merger of three small houses. In front of the gate of the main house of the count of Cifuentes a square was opened in the final quarter of the 15th century on the plot of the synagogue since the latter had disappeared owing to ruin or intentional destruction.

The synagogue

The synagogue (place of congregation, in Greek) is a Jewish temple. It faces Jerusalem, the Holy City, and it is a place for religious ceremonies, communal prayer, studying and meeting.

The Torahis read at the ceremonies. This task is conducted by the Rabbis aided by the cohen or singing child. The synagogue is not only a house of prayer but also an instruction centre as it is there where the Talmudic schools are usually run.

Men and women sit in separate sections.

The synagogue interior contains:

- The Hejal closet located in the east wall, facing Jerusalem, stored inside the Sefer Torah, the scrolls of the Torah, the Jewish sacred law.

- The Ner Tamid, the everlasting flame always lit before the Ark.

- The menorah, a seven-armed candelabrum, a habitual symbol in worship.

- The Bimah, place from where the Torah is read.

Cambrón Gate

The Cambrón gate or Bab al-Yahud (Gate of the Jews) of the original Jewish quarter, the main entrance and exit of the Jewish quarter and of the city via the west, is a highly modified gate of Moslem origin. Its location coincides with the south-eastern limit of the former Jewish quarter of Toledo.

The current version dates from 1576 and it was structured by repeating the Bisagra structure, in square form based on a small interior courtyard surrounded by four towers covered by slate chapters. It has fragments with Roman reliefs similar to those of the Sol gate.

On both sides there are Renaissance gateways with coats-of-arms, that of the city on the exterior and that of Felipe II on the interior. Under the latter a beautiful image of St.Leocadia can be seen, the patron saint of Toledo. The gate also bears the inscription reminding that the residents of Montes de Toledo, part of the city, are except from passage rights. Its name is associated with brambles, thornyplants which are abundant in the area.

Catedral

Church of Santo Tomé

Former souk or market

At San Antonio square alongside the church of Santo Tomé was the site for centuries of a market and meeting place between Jews and Christians. Here, at the end of Santo Tomé street, the souk or market was held.

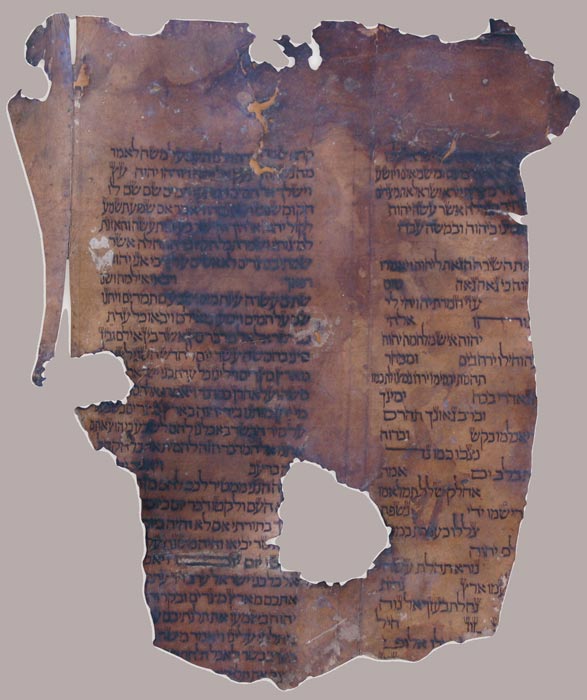

Fragment of Sefer Torah

Some works at a house in Toledo brought to light this fragment of the Sefer Torah with the text of Exodus 14, 29 to 15, 14, concealed by a walling-up in the late 15th century or in the 16th century. This concealment can be put down to fear of the Inquisition, though it has not been ruled out that it could reflect the Jewish practice of burying the holy text once the document can no longer be used.

The parchment was discovered in 2006 by the archaeologist A. Ruiz Taboada during the course of some excavations carried out on some works at number 3 of Travesía de los Caños de Oro. It was hidden inside a niche behind one of the notched panels of a bricked up horseshoe arch of what must have been a house in the Jewish quarter. It seems that the last remodelling of this arch was carried out in the late Middle Ages which would leave us to believe that it may have been at this time when it was deposited there. Archaeological evidence would thus seem to indicate that the concealment occurred between the 15th and 16th centuries.

The concealment of this type of documents, a relatively frequent occurrence, usually involves converts and it is attributed to their alleged desire to conceal the document owing to fear of the Inquisition. However, what is for sure is that it is unknown who the owners were and exactly why this fragment was buried in the wall. It is possible that in view of the Jewish tradition to put documents in genizot (though the place where it was found was not exactly a genizah), the aforementioned fragment was walled in so it wouldn´t be destroyed, thereby complying with the «burial» of the biblical text. The fragment can currently be found in the collection of the Santa CruzMuseum in Toledo.

Golondrinas (Swallows) Synagogue

The archaeological excavations of 2006 at the house at number 29 of Bulas street confirm the existence of an old synagogue alongside the house which formed a corner with Bulas street and the entrance to the former Golondrinos alley. Jean Passini refers to it as the synagogue de los Golondrinos (of the swallows).

In the second half of the 15th century a synagogue is mentioned, using it as a point of reference in the description of two houses in the parish of San Román. The first, which belonged to don Abraham batidor, was erected on the wall-walks of Sancho Padilla (the current Esquivias alley). It adjoined the house of the silk dealer Diego López and at the rear, a Jewish synagogue. The second house belonged in 1488 to a converted Jew, Lope de Acre. It is described at that time on the wall-walks of los Golondrinos, having a dividing wall with a yard which used to be a synagogue of the Jews. The Libro de Capellanias (Book of Chaplaincies) dated 1577 states that the house stood at the corner of Bulas street-Golondrinos alley. The ownership deeds of the monastery also state that it had a cellar under it with its door opening out onto Bulas street, a door which still existed until 2009.

Along with the remains of the synagogue, the remains have been found of a ritual bath or Mikveh, which we can compare with that Besalú, a closed space, endowed with solid walls, stone arches and water piping which consisted of a small room with a barrel vault, accessible from the street via an independent gate. An underground system, certified by the existence in the vicinity of a well called Aizco, supplied the running water required. An interior side corridor allowed passage from the vaulted room to the synagogue.

The synagogue

The synagogue (place of congregation, in Greek) is a Jewish temple. It faces Jerusalem, the Holy City, and it is a place for religious ceremonies, communal prayer, studying and meeting.

The Torahis read at the ceremonies. This task is conducted by the Rabbis aided by the cohen or singing child. The synagogue is not only a house of prayer but also an instruction centre as it is there where the Talmudic schools are usually run.

Men and women sit in separate sections.

The synagogue interior contains:

- The Hejal closet located in the east wall, facing Jerusalem, stored inside the Sefer Torah, the scrolls of the Torah, the Jewish sacred law.

- The Ner Tamid, the everlasting flame always lit before the Ark.

- The menorah, a seven-armed candelabrum, a habitual symbol in worship.

- The Bimah, place from where the Torah is read.

Hamanzeite District

Situated between Horno street (now San Juan de Dios street), Conde square, Cuesta de los Alamillos and the southwest wall of the Jewish quarter, the Hamanzeite district had larger houses than those of the district near Montichel or Assuica in the vicinity of the Tránsito synagogue.

House of Samuel Ha-Levi

The statue of Samuel Ha-Levi Abulafia on Paseo del Tránsito pays homage to this great Toledan character to whom we owe the construction of the Tránsito synagogue. Behind the statue, opposite the synagogue, there lies the large architectonic unit of the house-palace of Samuel Ha-Levi. Part is used today to accommodate the El Greco Museum.

Samuel Ha-Leví

Samuel Ha-Levi Abulafia, a public employee, a High Court Judge and Royal Treasurer with Pedro I of Castile, was a member of an influential family who acted as a fully empowered administrator for the Portuguese knight Juan Alfonso de Alburquerque before coming under the orders of King Pedro I to reorganise Castile´s finances.

A refined man with a knowledge of astrology and divination, he held different posts in the Court and played a decisive role in the establishment of Pedro I the Cruel against his bastard brothers Trastámara.

The notable influence and rapid growth of wealth meant that the treasurer obtained the King´s permission to build another synagogue despite papal prohibition.

His greatest recompense was the returning to the Jews of assets they had lost after the sacking of the Jewish quarter of 1355 by the supporters of the Trastámara and, in particular, the construction of the splendid synagogue which bore his name. However, this powerful magnate barely lived three years to enjoy his achievements as, accused of swindling the royal treasury, he didn´t survive the torture he had to endure in 1361.

House of the Jew

At number 4 of Travesía de la Juderia is the dwelling known as the house of the Jew. Legend has it that this house belonged to the Jew Ishaq who provided money to queen Isabel the Catholic in exchange for her jewels to fund Columbus´ voyage to America.

This is a dwelling whose origins can be dated back to the 14th to 15thcenturies with Mudejar reminiscences and possible Jewish liturgical used, accompanied by adaptations and transformations in the subsequent centuries. The courtyard conserves a multitude of plasterwork with horseshoe arches and rich Mudejar latticework. In the cellar there is a liturgical Jewish bath or Mikveh which was used for spiritual purification and preparation for any important event in the life of a Jew. During its restoration hydraulic rough plastering on the ochre and a rainwater tank were discovered in adjoining rooms which help to back up the theory about its use.

Another highly relevant element for its archaeological study is a wooden piece used as lintel for access to the cave where the carving work with floral motifs can be observed based on tympanums and scrolls, accompanying an epigraphic repertoire whose transcription reads:

Text related with verse 21 and subsequent verses of Psalm 118:

This text welcomed all the faithful and chaste into the interior of the house.

The mikveh, the Jewish bath of purification

The Mikveh, the Jewish bath of purification, is an essential building in any Jewish community. Its functionality is the spiritual purification through total immersion of the body in the water and this is why it accompanies all the most important acts in the life of a Jew. The Jewish woman purifies herself after menstruation when she has to have a child and when she has already had one and both the bride and the groom right before the wedding. Converts to Judaism must be immersed in the bath and also anyone who has been in contact with contagious illnesses or impurities.

The person must be prepared for the act of purification. He/she must have washed and combed first so that the water totally impregnates them. The immersion is carried out three times to ensure this is the case. Men are usually purified on Fridays before sunset before the start of the Shabbat or day dedicated to God.

Jewish butcher´s

At the end of the 13th century there was a square in the Arriaza district, opposite the Old Castle where the butcher´s shops were located.

From an urban perspective, the butcher´s was a closed space which had at least one main gate.

In the assets´ inventory for the Jewish aljama of 1494 we can see that the Jewish butcher´s encompassed at least six houses which were together, a farmyard, several gates, a hospital, a plot between two towers and, what´s more, a main gate. Despite this information, we do not have any document prior to 1492 allowing us to specify the place where the butcher´s was located.

After the Decree of expulsion, some major dignitaries of the city, deprived of the taxes they received from the houses subject to tax, abandoned by their Jewish residents, asked the monarchs for compensation. These requests included the figure of alderman Fernando Dávalos, his brother Alonso and Fernán Suárez answered by the Catholic Monarchs in March 1494, ordering their advisor and Chief Magistrate of Toledo to grant them the right to sellthe old synagogue which the Jews had in said city, near the Jewish butcher´s with all the houses annexed and belonging to them in compensation for the losses suffered.

The butcher´s

The meat eaten by the Jews had to be slaughtered according to a very strict religious ritual. This was carried out at the slaughterhouse and the meat was sold at the butcher´s.

The slaughterhouse, market or scaffold was a space which acquired a certain ritual nature by dint of the liturgy ( shejitah ) undertaken there whilst slaughtering animals whose meat was intended for human consumption (kosherfood). The norm was for the slaughterhouse to be located in an area on the outskirts of the Jewish quarter to avoid unpleasant odours in the city.

The meat was sold at the butcher´s where sales points were erected which were let out. The income obtained was used for certain needs of the aljama.

Jewish cemetery

Situated at Cerro de la Horca (Hill of the Gallows), its perimeter and slightly beyond is today occupied by a Secondary Education Institute.

Sources mention two burial places for the Jewish community outside the walls of the city: The Pradillo de San Bartolomé (around the Roman circus) and the Cerro de La Horca. The full extent and exact location of these two necropolises is not known, although we do have material record of its existence from the collection of monolithic headstones with inscriptions, spread throughout the city either in museums or forming part of the foundations of some Gothic monuments. This indicates at least two burial areas for the Jewish community which can perhaps be put down to the increase in population which occurred as from 1085 and, in particular, from the mid-12th century and during the 13th century with the Jews from Al-Andalus fleeing Almohad persecution.

Excavations were carried out in 1887 and some tombs were removed which are to be found today at the Sephardi Museum and the National Archaeological Museum of Madrid.In 1979 the contractor intentionally destroyed part of the necropolis during the construction of the Secondary Education Institute.During 2008 and 2009 new archaeological excavations were carried out in a sector of the necropolis which made clear that the burial patterns at Cerro de La Horca do not correspond to anything known up to that date in Toledo during the Middle Ages, leading us to think that this may actually be the site of one of the Jewish necropolises of Toledo.

The cemetery

The cemetery was located outside the walls at a certain distance from the Jewish district. The chosen site:

- Must be on virgin soil

- Must be on a slope

- Be oriented towards Jerusalem

The Jewish quarter had to have a direct access to the cemetery to prevent the burials from having to pass through the interior of the city.

After 1492 the monarchs authorised (in Barcelona in 1391) the reuse of stones from Jewish cemeteriesas construction material. It is thus not unusual to find fragments of Hebrew inscriptions in several subsequent constructions.

Despite the pillaging they suffered from the late 14th century, the memory of these cemeteries has remained in the name in certain places, for instance, Montjuïc in Barcelona or Girona. We are aware of the existence of more than twenty medieval Jewish cemeteries. Others are only known of thanks to the documentation or the headstones conserved. The one in Barcelona at Montjuïc was excavated in 1945 and 2000, the one in Seville in 2004, the one in Toledo in 2009 and the one in Ávila in 2012.

Jewish headstone on Plata street

Plata street is made up of houses of fine construction with large entrance gates and sculptural details. The house at number 9 has as its lintel a Jewish headstone bearing an almost totally faded inscription. The adornment of the balls and cordon is typical of the time of the Catholic Monarchs.

It was on this street where the jeweller were concentrated, in the main Jews, very good silversmiths, along with other Christian craftsmen.

Knights of Calatrava Convent-Sephardi Museum

The Sephardi Museum in the city of Toledo occupies the site of the Knights of Calatrava Convent, annexed to the Tránsito Synagogue. It is the NationalMuseum of Hispano-Jewish and Sephardi Art and it accommodates a large amount of traces of the Jewish culture.

The Sephardi Museum is made up of five rooms which display disappeared, religious and local customs and manners aspects of the Jewish past in Spain as well as of the Sephardis.

The rooms adjoining the synagogue and the restored courtyard today house displays of the uninterrupted Jewish presence in Spain since time immemorial as well as elements of the Sephardi culture, in other words, of the Spanish Jews spread around the world after their expulsion in 1492.

The northern courtyard displays, by way of a necropolis, some of the tomb headstones with Hebrew inscriptions conserved at the museum. They were previously on show inside the building, but in the latest remodelling they were displayed outside, thereby going to make up a Jardín de la Memoria (Garden of Memory) which is also converted into a rest area.

The material deployed to make the headstones varies in line with the place of origin. The marble ones, less common, are prevalent in Castile and León; the limestone and sandstone ones, easier to work on, are the most frequent and are particularly common in all the necropolises of Girona and Barcelona. In Toledo the predominant material is granite, though there is no lack of epitaphs made of the previous materials; the museum has a headstone made of baked clay.

At the eastern courtyard an array of bronze sculptures are on display by contemporary artists (Martina Lasry and David Aronson) as well as a slate headstone of a Calatravan knight from the 16th century. The courtyard serves as a link between the lower rooms of the museum and the Women´s Gallery. Excavations carried out under the ground have brought to light various rooms identified as water tanks or rainwater tanks.

The old Women´s gallery is dedicated to the life and festive cycles and other expressions of Sephardi culture.

Midrash of the beams

The inventory of 1495 of the assets of the Jewish community (the aljama) with regard to which the numerous nobles of Toledo received taxes, confirms the existence in the Middle Ages of a study house or midrash in the Jewish district of Alacava. In actual fact, we are aware of a document which states that:

No data has been obtained serving to precisely situate its location in the district. A document dated 1558 says that the house called Midraz de las vigas is on the wall-walks of Bernardo de los Pleytos as the Cuesta de Bisbís was called at this time in the 16th century.

The midrash de las Vigas is described in 1564 as a large house with a courtyard with three or four storeys, two palaces on the ground floor, gangways on the four sides on the first floor and a cellar under one of the palaces. It was in the block extending between Caños de Oro street and the Cuesta de Bisbís, a block in which there was also a house of prayer belonging to the aljama. In the same block in 2006 a parchment was discovered with a fragment of the Torah, to be precise, in niche in the house at number 3 of Caños de Oro street, confirming the importance this block must have had in the religious life of the Jews of the Santo Tomé district.

Montichel District

The Montichel district corresponds to the area of Paseo de San Cristóbal and Calle de los Descalzos. The fence of Montichel was the wall of the Jewish quarter in this part.

From Salvador square Taller del Moro street outlines the limits of the city of the Jews in the south-eastern end of the Jewish quarter. The place where Descalzos road meets Paseo del Tránsito is also the confluence of two very different Jewish districts. To the south, around Descalzos street and Paseo de San Cristóbal was the district of Montichel, endowed with an intricate layout and humble houses. In Tránsito stood the district of Hamanzeite with noble houses of good standing.

New Castle of the Jews

The New Castle was a complementary defence of the new San Martín bridge, part of the exterior wall of the Jewish quarter, in the current Paseo de Recaredo which rises up to the Cambrón gate, built by the Arab governor from Toledo Muhachir ibn Al-Qatil in 820.

The castle

Inside some Jewish quarters there was a so-called castleand even two, as is the case of Toledo, though it is possible that the New Castle in Toledo was built when the Old one was no longer usable.

The meaning of this fortress in the interior of the Jewish quarter is unknown.

It may be a defensive construction against attacks on the Jewish quarter or a construction materializing the presence of the corresponding power to which the Jewish quarter was subject.

Old Castle of the Jews

The castle´s purpose was to protect the neighbouring districts and the inhabitants of the Jewish quarter in the event of attack as occurred in 1355. A small number of documents mention it before the 15th century. The «castle of the Jews» features in 1163 in the deed for a loan granted to the Jew Isaac ben Abuyusef which cites as collateral half of his house in the castle of the Jews over the River Tagus. A century later there is mention of a street stretching from the Castillo Viejo gate of the Jewish quarter to the Castillo Nuevo gate. In 1492 further mention is made in a tax acceptance document regarding a house near the castle bordering certain houses and the synagogue of Santa María la Blanca and the «calle real (royal street)».

The «Castillo Viejo (Old Castle)» features on the list of assets of the aljama in Toledo in 1492: the castle adjoined the butcher´s and the slopes which went down to the Tagus; one of its towers stood alongside the butcher´s door and the «public streets». On this date all that was left of it was a plot and a tower. In 1496, seeing that this whole space was todo fecho muladares e syn provecho, the employees who inspected it by order of the monarchs thought que en fasello casas se farya barryo poblado, e quedava calle tan ancha y mas que ninguna de la dicha çibdad. In this way the plot which the castle had previously occupied was divided up into parcels and houses were built on the latter in the first quarter of the 16th century.

The castle

Inside some Jewish quarters there was a so-called castleand even two, as is the case of Toledo, though it is possible that the New Castle in Toledo was built when the Old one was no longer usable.

The meaning of this fortress in the interior of the Jewish quarter is unknown.

It may be a defensive construction against attacks on the Jewish quarter or a construction materializing the presence of the corresponding power to which the Jewish quarter was subject.

Old synagogue

The Old Synagogue was in the Jewish butcher´s area, between the latter and the wall which looms over the Tagus. The synagogue was seriously damaged during the uprisings in summer 1391.

The old synagogue was replaced in the 16th century with a house which was known as «deep house».

The synagogue

The synagogue (place of congregation, in Greek) is a Jewish temple. It faces Jerusalem, the Holy City, and it is a place for religious ceremonies, communal prayer, studying and meeting.

The Torahis read at the ceremonies. This task is conducted by the Rabbis aided by the cohen or singing child. The synagogue is not only a house of prayer but also an instruction centre as it is there where the Talmudic schools are usually run.

Men and women sit in separate sections.

The synagogue interior contains:

- The Hejal closet located in the east wall, facing Jerusalem, stored inside the Sefer Torah, the scrolls of the Torah, the Jewish sacred law.

- The Ner Tamid, the everlasting flame always lit before the Ark.

- The menorah, a seven-armed candelabrum, a habitual symbol in worship.

- The Bimah, place from where the Torah is read.

Original Jewish quarter

The area around the Bajada de San Martín was the originalMadinat al-yahud (City of the Jews) assigned to them by the Arabs between the gate of the Jews (Cambrón Gate) and San Martín bridge (San Martín district). It was subsequently called Degolladero or Degolladera (Slaughterhouse) of the Jews, becoming a highly inhabited district, undoubtedly owing to the presence of the slaughterhouse in this segregated area.

More or less in the space where the Cava palace is erected, the Assuica district has taken over from the original Jewish quarter, the true madinat al-Yahud where the Moslems settled the Jews before the Christian conquest between the gate of the Jews and or Cambrón and the San Martín bridge with its main route on the current Bajada de San Martín. Little remains of the old Jewish quarter except for the structure of the streets, still on uneven ground, and the remains of the walled defences such as the so-called New Castle of the Jews or the exterior wall of the Jewish quarter as the current Paseo de Recaredo, which rises up to Cambrón gate, built by the Arab governor from Toledo Muhachir ibn Al-Qatil in 820. The steps of Alamillos de San Martín alley descend steeply as far as the Bajada de San Martín at the end of which was the Portiel gate in a district which popular memory has recalled as the Degolladero or Matadero Judío (Jewish slaughterhouse).

The butcher´s

The meat eaten by the Jews had to be slaughtered according to a very strict religious ritual. This was carried out at the slaughterhouse and the meat was sold at the butcher´s.

The slaughterhouse, market or scaffold was a space which acquired a certain ritual nature by dint of the liturgy ( shejitah ) undertaken there whilst slaughtering animals whose meat was intended for human consumption (kosherfood). The norm was for the slaughterhouse to be located in an area on the outskirts of the Jewish quarter to avoid unpleasant odours in the city.

The meat was sold at the butcher´s where sales points were erected which were let out. The income obtained was used for certain needs of the aljama.

Portiel Gate or Wicket Gate

Gate located further up from the San Martín bridge, providing access to the original Jewish quartervia Grande street (the current Bajada de San Martín). From a small cul-de-sac alongside gate a path went up to the Almaliquim synagogue. This path went up via the lower area of the current Alamillos de San Martín and followed via Mármol street (the old street which probably ran between the monastery and the San Juan de los Reyes garden) and the marble lean-to, leaving on the right the path and wall-walks of the castles. It then went up Santa Ana street as far as the Santa María La Blanca synagogue.

Samuel Leví street

Between the house of Samuel Ha-Levi and the Tránsito synagogue there lies Samuel Levístreet where part of the houses of the owner of this street was transformed in 1909 into the Museum of Doménico Theotocópuli, El Greco. Alongside the former gate which closed off the street, a tile recalls the painful legend of Samuel Ha-Levi which forms part of the mythology of Toledo.

Samuel Ha-Leví

Samuel Ha-Levi Abulafia, a public employee, a High Court Judge and Royal Treasurer with Pedro I of Castile, was a member of an influential family who acted as a fully empowered administrator for the Portuguese knight Juan Alfonso de Alburquerque before coming under the orders of King Pedro I to reorganise Castile´s finances.

A refined man with a knowledge of astrology and divination, he held different posts in the Court and played a decisive role in the establishment of Pedro I the Cruel against his bastard brothers Trastámara.

The notable influence and rapid growth of wealth meant that the treasurer obtained the King´s permission to build another synagogue despite papal prohibition.

His greatest recompense was the returning to the Jews of assets they had lost after the sacking of the Jewish quarter of 1355 by the supporters of the Trastámara and, in particular, the construction of the splendid synagogue which bore his name. However, this powerful magnate barely lived three years to enjoy his achievements as, accused of swindling the royal treasury, he didn´t survive the torture he had to endure in 1361.

San Juan de Dios street

San Juan de Dios street, the former Horno street, is one of the main thoroughfares of the Hamanzeite district and its layout opens out into various culs-de-sac before connecting to Travesía de Santo Tomé. The house at number 18 is again related with the existence of some baths and that at number 8 with its elegant lintel serves as an example to illustrate the nobility of a district in which Jews of good standing lived.

The oven

During the Middle Ages the ovens of the cities were of a public nature and could only be built or used under royal license. It was the norm for there to be at least one oven in each Jewish quarter at which bread was baked for daily consumption.

From an architectonic perspective, the Jewish oven had to be similar to those raised in other parts of the city: Making bread was not subject to any specific kind of ritual and hence the oven was not subject to any different aspect in its construction. This also means that a Jew could buy bread from a Christian or use a Christian oven to bake bread without transgressing any rules.

During the Passover unleavened bread was baked (matzah), without yeast, whose dough bore a seal. As it was a special kind of bread, in Jewish quarters where there was no oven, temporary ones could be built to bake it.

San Juan de los Reyes

The monastery of San Juan de los Reyes began to be built in 1477 by order of Queen Isabel the Catholic to commemorate her victory at the battle of Toro in 1476. Its monumental presence right in the heart of the Jewish quarter in the traditional environment en where the Jewish market of the Assuica district was situated is highly symbolic. The Catholic Monarchs were initially the only source of refuge for the Jewish communities before the persecutions which occurred in the late 15th century yet it was they who signed the Decree of expulsion of 1492, thereby putting a permanent end to a long period of cohabitation between Jews, Moslems and Christians.

The convent´s austerity contrasts with the grandiosity of the church, adorned by spacious large windows, arches and Gothic pinnacles, on whose walls the chains of the Christian convicts which had hung there since 1494 when the Catholic Monarchs recovered them after the conquest of Granada.

The church was built to house the dynastic pantheon of Queen Isabel the Catholic dedicated to St.John the Evangelist of she was a devotee. Finally, the monarchs changed their mind after the conquest of Granada and they are buried in the Royal Chapel of the cathedral of this city.

Another key space is the square, two-storeyed cloister, one of the masterpieces of late Gothic within Hispano-Flemish aesthetics which combines Gothic and Mudejar elements. The upper cloister has a wooden coffered ceiling with the typical Mudejar latticework.

The convent was practically destroyed in the war of Independence and was only partly rebuilt, with the second cloister disappearing according to historicist criteria of the 19th century, leaving no distinction between the old and the restored one, the best example of which is the gargoyles of the cloister.

San Martín Bridge

From the other side of the San Martín bridge, alongside the waters of the Tagus, the view of the city, from the heights on that side, provided a better understanding of the complex, difficult and at the same time fascinating history of a Jewish quarter like that of Toledo. A Jewish quarter where the keys of the houses of those who had gone into exile in 1492 had become the greatest symbol of the Sephardi nostalgia.

The Jewish quarter of Degolladero largely coincided with the current Reyes Católicos street and the San Martín bridge and river. It bore this name because this was the site of the Jewish butcher´s where the poultry and cattle were slaughtered. A statue of Isabel the Catholic (1451-1504), the Queen of Castile, was located at Reyes Católicos street, very near the monastery of San Juan de los Reyes. Under the edict of expulsion of 1492 the Catholic Monarchs sent between 170,000 and 180,000 Sephardis into exile.

Santa María la Blanca Synagogue

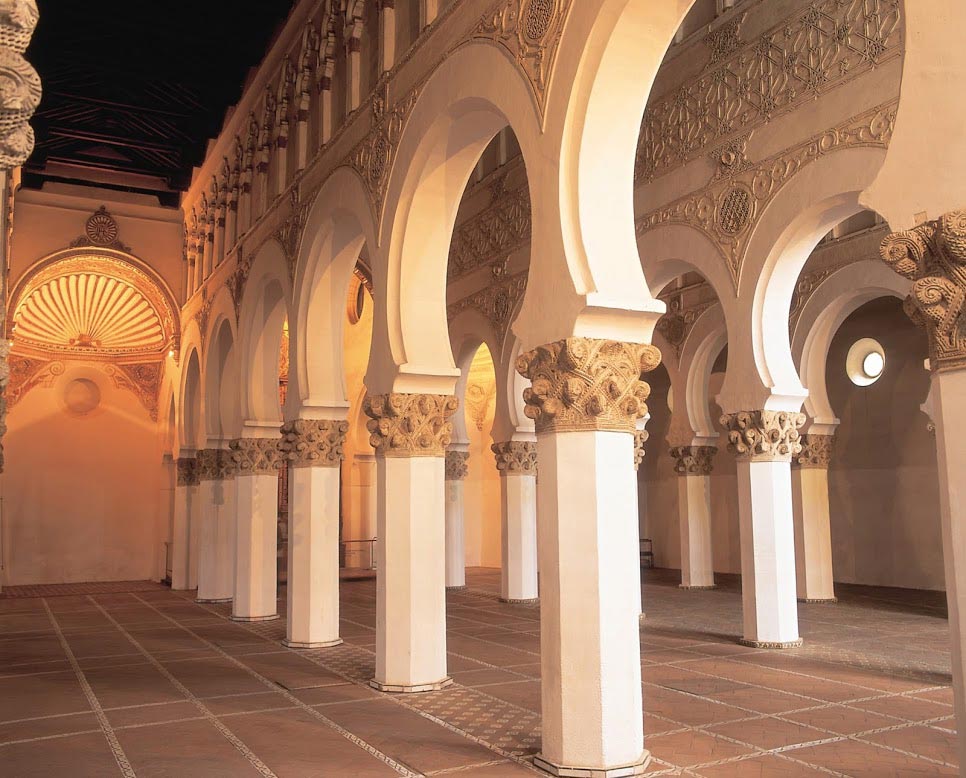

The Synagogue of Yosef ben Shoshan from the early 13th century was provided by Alfonso VIII, a monarch who was clearly sympathetic towards the Jews. In 1411, after the sermons by Vincent Ferrer, it became a Christian temple and since that time it was known as the church of St.Mary the White. In 1550, after introducing some remodelling work, cardinal Silíceo used the temple to create a beaterium for women who had publicly repented. In the 18th century the building was converted into a military barracks and in the mid-19th century it began to be recovered as an artistic monument.

A large door opening out onto Reyes Católicos street and a simple garden precede the entrance to the synagogue. It is erected on a courtyard surrounded by cypresses where the main door is situated with star-shaped Mudejar latticework under a pentice. In the subsoil there are vaults used for burials since the 16th century and other archaeological remains.

Once again the humble exterior appearance contrasts with the grandiosity of its interior. Five naves separated by horseshoe arches, octagonal columns with chapters adorned by pine cones and volutes, adapt to an asymmetric layout which is more reminiscent of a mosque than a synagogue. On these arcades there are some decorative borders with geometric and vegetal elements which follow a perfectly defined rhythm in the spandrels of the arches. Poly-lobed arches are used to raise the central nave, leaving the side decks lower down with their attendant coffered ceilings. The whole structure is catalogued as an example of Almohad art put to the service of the Jewish community.

In the 16th century Alonso de Covarrubias, at the behest of cardinal Silíceo, remodelled the heads, creating three chapels, the central one lined with a half orange-shaped vault on tubes whilst the sides are a quarter of a circle over Pechinas. The retable is by Nicolás Vergara, the Old Man, carried out in the second half of the XVI.

The synagogue, in the same way as the Tránsito one, has undergone numerous ups and downs during the course of its history. Not waiting for the decree of expulsion by the Catholic Monarchs, it is said that the sermons of Vincent Ferrer from the pulpit of Santiago del Arrabal led to the Christians taking the temple in 1411 and they expelled the Jews from it, turning it into a church dedicated to Santa María la Blanca. An old legend has it that the temple was built from earth brought from Jerusalem.

The synagogue

The synagogue (place of congregation, in Greek) is a Jewish temple. It faces Jerusalem, the Holy City, and it is a place for religious ceremonies, communal prayer, studying and meeting.

The Torahis read at the ceremonies. This task is conducted by the Rabbis aided by the cohen or singing child. The synagogue is not only a house of prayer but also an instruction centre as it is there where the Talmudic schools are usually run.

Men and women sit in separate sections.

The synagogue interior contains:

- The Hejal closet located in the east wall, facing Jerusalem, stored inside the Sefer Torah, the scrolls of the Torah, the Jewish sacred law.

- The Ner Tamid, the everlasting flame always lit before the Ark.

- The menorah, a seven-armed candelabrum, a habitual symbol in worship.

- The Bimah, place from where the Torah is read.

Santo Tomé District

Commercial, noisy, rife with monuments and historic, but also tourist and gastronomic references, Santo Tomé street is not only the centre of the Santo Tomé district, but also one of the main thoroughfares of the Jewish quarter.

The Santo Tomé district was a well-to-do Jewish area where Christians lived too. It encompassed a large part of Santo Tomé street, the current Conde square and the first part of Alamillos and San Juan de Dios streets. In documents from the 15th century the main gate of the Jewish quarter in this district is mentioned.

The church of Santo Tomé where the mythical painting by El Greco El entierro del Señor de Orgaz (The burial of the Count of Orgaz) is on display or the San Antonio convent at whose reception you can buy delicious sweets, are two major references on this street into which some alleys flow like Campana or Soledad which lend us some idea of the way in which the Jewish labyrinth was organized around the main streets of madinat al-Yahud.

Sofer synagogue

SoferSynagogue (Hebrew for Scribe) was probably built in the late 12th century or early 13th century. In 1391 Suleimán Jarada had a house known as the Higuera (fig tree) between the Atahona house and the Sofersynagogue. It would seem that the Sofer synagogue, the Higuera house and the Atahona house formed an architectonic unit between Ángel street and Reyes Católicos street. The Sofersynagogue probably stopped being used for this purpose in 1391 after the unrest and attacks the Jews were subject to and which brought about the departure of don Sulemán. We don´t what happened to it as it not mentioned again after 1480. According to an order by the Catholic Monarchs it could not be put up for sale nor occupied after the expulsion of the Jews. The attendant wall of the synagogue - which still existed in the 16th century opposite the second cloister of San Juan de los Reyes as can be seen in the El Greco plan - disappeared in the second half of the 19th century. It left its mark as a quadrangular square in 1858 in the Coello plan.

Excavated during 2011, the existing archaeological remains are currently visible under Sofer square, inaugurated in 2012.

The synagogue

The synagogue (place of congregation, in Greek) is a Jewish temple. It faces Jerusalem, the Holy City, and it is a place for religious ceremonies, communal prayer, studying and meeting.

The Torahis read at the ceremonies. This task is conducted by the Rabbis aided by the cohen or singing child. The synagogue is not only a house of prayer but also an instruction centre as it is there where the Talmudic schools are usually run.

Men and women sit in separate sections.

The synagogue interior contains:

- The Hejal closet located in the east wall, facing Jerusalem, stored inside the Sefer Torah, the scrolls of the Torah, the Jewish sacred law.

- The Ner Tamid, the everlasting flame always lit before the Ark.

- The menorah, a seven-armed candelabrum, a habitual symbol in worship.

- The Bimah, place from where the Torah is read.

The Alcaná

Famous amongst the commercial streets was the alcaná of Toledo which brought together the most select commerce and which, even after the Jews were expelled, was still a designated place. The alcaná of Toledo was in the minorJewish quarterof the Middle Ages.

During the Islamic period the shops situated around the main mosque were grouped on some streets which were closed at night. This set was designated by the name of alcaicería. The term alcaicería is still used in the 12th century in a donation document. As from the 12th century, the shops – in Arab, aljanat – are called by their Hispanized name: the Alcaná of Toledo was known throughout Spain.

The Alcaná features in numerous sale or donation documents pertaining to houses throughout the 13th century. In 1218, for example, the archbishop of Toledo donated to a relative of Pope Honorius III all the shops he owned in the alcaná infra muros Toltane ciuitatis. A cathedral document in 1234 mentioned that the chapterhouse had twenty five shops there and an inn. In 1283 we can read that a house was sold near the Alcaná and the street near the church of the Holy Trinity.

The area it occupied at the end of the 12th century and during the course of the 13th century is unknown. In the 14th century the term Alcaná designated the commercial district alongside Toledo cathedral where archbishop Pedro Tenorio intended to build the cloister of the cathedral. A fire destroyed the majority of the shops and their occupants had to be accommodated in the shops on Atalares street.

This fire facilitated the availability of the sites required to build the Cloister. In addition Pedro Tenorio´s Project, a further one was added regarding a chapel dedicated to San Blas and he financed it by buying for the chapel eighty four shops of the King and the shops of the clerks provided by don Lope and his wife doña Fátima, the Moorish maid of Queen Juana, the wife of Enrique III. The shops of the king, situated at the Cuatro Calles (Four Streets), backing onto each other at Atalares street, were distributed between the Blacksmith´s to the north, the clerks´ school and the church of Santa Justa to the west; Cuatro Calles square, to the south, and finally, the Tannery and Draper´s to the east.

The Alcaná in El Quijote

The Alcaná of Toledo is mentioned by Miguel de Cervantes in a key passage of El Quijote in chapter IX of the first part where the author whisks us away to this old area of Toledo:

Toledo Translators´ School

The Toledo Translators´ School brought together the group of Christian, Jew and Moslem scholars which undertook very important scientific and cultural work in Toledo, particularly in the reign of Alfonso X the Wise (1252-1284) when it attained its greatest splendour.

Its toil allowed the works of ancient Greek culture which covered the fields of geography, astronomy, cartography, philology, philosophy, theology, medicine, arithmetics, astrology or botanics were brought out of oblivion and conveyed to medieval Europe via the Peninsula. This is why the school was the origin and base for the scientific and philosophical Renaissance of Western culture.

The School started in the 12th century, a time when it mainly specialised in philosophical and theological texts (Domingo Gundisalvo interpreted and translated the comments of Aristotle – written in Arab - into Latin which Juan Hispano, a Jewish convert, had previously translated into Spanish). As far back as the first half of the 13th century, during the reign of Fernando III, the Libro de los Doce Sabios (Book of the Twelve Wise Men ) (1237) was written, a summary of classical moral and political wisdom drafted by «oriental» hands.

Its origins can be found in the Jewish emigration en masse from Al-Ándalus to the Christian kingdoms and the cultural renaissance this took with it. Toledo was settled by poets, grammaticians, philosophers, scientists, doctors and other learned men, making the city their main destination. The Archbishop of Toledo don Raimundo de Sauvetat, who later became the Chancellor of Castile with Alfonso VII, wished to take advantage of the climate which allowed Christians, Moslems and Jews to live in harmony, provided his backing to different translation projects requested by all the courts of Christian Europe. The prestige of the School of Translators of Toledo was so great that not even the anti-Jewish stipulations of the Lateran Council in 1215 could stop it from flourishing.

Alfonso X the Wise and the Toledo Translators´ School

Under Alfonso X the Wise the School gained in importance thanks to royal support of translation activity. He situated the School in the cellars of the astronomic observatory, located at the current site of the Seminar alongside the parish church of San Andrés, naming as a functionary of the School Zag ibn Sid, the compiler of the Tablas Alfonsíes (Alfonsíes Tables). The Tablas contain the observations made in the firmament in Toledo from January 1st 1263 to 1272 and which record the movement of the respective celestial bodies on the ecliptic with precise positions. Major works on astronomy were also translated from Arab to Castilian Spanish by Yehuda ibn Moses Cohen, the presumed translator of the book of magic known as Picatrix as well as men of great intellectual standing like Samuel Ha-Levi Abulafiaand Abraham Alfati who carried out lucid versions from Arab or Hebrew into the Romance languages and into Latin by Christian translators.

Travesía de la Juderia/Jacintos Alley

Alongside the House of Jacob, which has now disappeared, a bookshop specialised in Jewish matters, on Ángel street, there stand the steps which go down to the corner formed by callejón de los Jacintos and Travesía de la Juderia, two narrow roads which go round the rear of the synagogue of Santa María la Blanca. The latter comes out onto Barrio Nuevo square, given this name after the expulsion of 1492 where the Jewish market of the Assuica district was traditionally situated.

Legend of Jacintos Alley

Jacintos alley, alongside the walls of Santa María la Blanca, was the site of the legend regarding the love between the Jewess Salomé and Don Diego de Sandoval, a Christian knight which, yet again, ended in tragedy.

Don Diego de Sandoval was nicknamed the Jew with great contempt by nobles and commoners owing to the love he showed to Salomé, the Jewess, who proved elusive and cold and rejects his advances.

One night, Don Diego is approaching Jacintos alley where Salomé lives. He calls her from outside but she doesn´t reply nor does she open the balcony of her bedroom. Angry, Don Diego wishes to know the reason for this affront. He gathers a bunch of hyacinths and with the handle of his dagger he knocks on the large window, but Salomé doesn´t want to open it... and suddenly, a commotion and the Duke of Sandoval fall to the ground badly wounded. The hyacinths tinge with white the red pool of blood gushing from his wound.

The legend says:

everyone asked who

had killed the duke that night;

some say he did it himself,

others: No, it was the Devil,

and others still: Divine punishment.

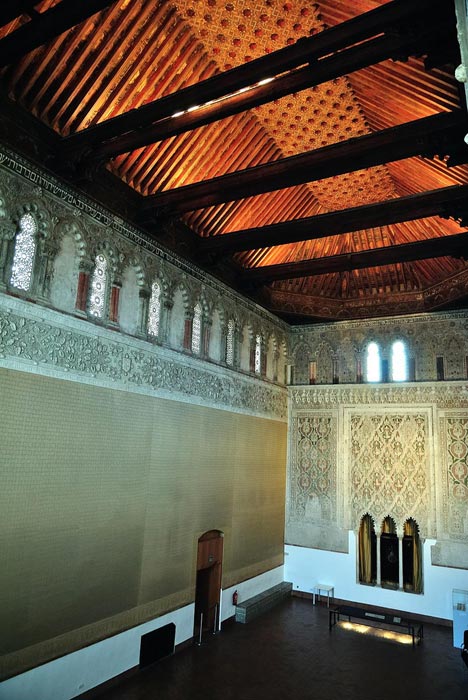

Tránsito synagogue

Built between 1355 and 1357 under the auspices of King Pedro I of Castile by his treasurer, the powerful Samuel Ha-Levi, the Tránsito synagogue was erected in the heart of the Jewish district of Hamanzeite. Its façade has undergone many modifications, not preparing us for the magnificence that lies within. The affected touch of the Mudejar master builders is all too evident and the block as a whole is organised from a large prayer room flanked by an upper gallery from where women attended the ceremony and complemented by rooms dedicated to the Rabbinic school (today rooms of the museum) and an exterior courtyard where there are remains of a possible Mikveh with two rainwater tanks.

In the prayer room, whose roof is one of the best examples of medieval carpentry in Toledo, worthy of special note is the splendid plasterwork on the walls with texts in Hebrew and Arab and geometric and heraldic motifs from Castile and León, accompanied by inscriptions with the Psalms of David, particularly on the east wall where three slim lobed arches open out, holding the scrolls of the holy texts or heijal, surrounded by a rich, delicate panel with beautiful polychromed plasterwork.

In the upper part behind a frame with muqarnas we find a succession of poly-lobed arches with matched columns which extend along the sides as well as a frieze where heraldic motifs can be made out.

On the ground, before the earpiece wall, part of the flooring is conserved which the synagogue had originally. The main room deck is closed by a jointed rafter framework in Mudejar style.

Upon the expulsion of the Jews in 1492 the Catholic Monarchs granted to the Order of Calatrava

In 1494 the building stopped being used as a synagogue and became part of the Priory of San Benito, with the area occupying the Rabbinic school and the women´s gallery serving as a Hospital and asylum for the Calatravan knights. The old large prayer room became a Christian temple and burial place for some Calatravan knights, referred to in the documentation as the Church of San Benito.

With the passage of time, in the 16th century it ceased to fulfil the aforementioned purposes and became solely a church, building an entry door to the sacristy and an arcosolium used for worshiping am image of the Virgin Mary. A retable also backed onto the central body of the former heijal and the main altar was placed on the original floor of the synagogue.

In the 17th century the church of San Benito began to be known as the church of Nuestra Señora del Tránsito owing to the commission that a Calatravan knight had given to the painter of the Toledo school Juan Correa de Vivar for a painting of the Transit of Our Lady (today conserved at the National Prado Museum) which was placed in the arcosolium.

In the 18th century the decadence of the might of the military orders also affected the previously rich church of Nuestra Señora del Tránsito which is referred to in the documentation merely as a hermitage. During the Napoleonic wars it was used as a military barracks, suffering continuous deterioration for almost all of the 19th century and continuing to be used as a hermitage until the Disentailment. On May 1st 1877 it was declared a National Monument. Since that time various restorations were undertaken to relieve the poor state of the building.

The synagogue

The synagogue (place of congregation, in Greek) is a Jewish temple. It faces Jerusalem, the Holy City, and it is a place for religious ceremonies, communal prayer, studying and meeting.

The Torahis read at the ceremonies. This task is conducted by the Rabbis aided by the cohen or singing child. The synagogue is not only a house of prayer but also an instruction centre as it is there where the Talmudic schools are usually run.

Men and women sit in separate sections.

The synagogue interior contains:

- The Hejal closet located in the east wall, facing Jerusalem, stored inside the Sefer Torah, the scrolls of the Torah, the Jewish sacred law.

- The Ner Tamid, the everlasting flame always lit before the Ark.

- The menorah, a seven-armed candelabrum, a habitual symbol in worship.

- The Bimah, place from where the Torah is read.

Ueld Elazri Wall-walks

A document from 1270 mentions the wall-walks called Ueld Elazri in a street connecting to Assuica, extending as far as the wall-walks of Olivo and, in turn, to:

The Jews lived in and owned castles in medieval Spain. Some of these castles were big enough to contain houses within their walls such as the Jewish castle of Toledo as is borne out in a document dated 1163.

At the current Bajada de Santa Ana you can still find part of the walls which surrounded the Jewish quarter and the wall-walks which led to the New Castle of the Jews.

Upper suburb of the Jewish quarter

Destroyed in 1355 during the power struggles between Pedro I and his brother with the troops of Enrique II, the district of Alacava or upper suburb of the Jewish quarter formed a separate nucleus of the Jewish quarter and delimited by the current winding Bulas street and Naranjos alley, the former wall-walk of Ciruelo.

In 1456 the wall-walks of Caños de Oro were closed by a gate whose lean-to, already in ruins, was built in the 16th century. Even today its base is visible on the wall of the first house at the entrance to the street. The Cuesta de Bisbís, called wall-walks of wool dealers, afforded a very wide, paved entrance as seems to be indicated by the street name which was applied to it. A clear narrowing can be noted there where the gate of the street was whose lean-to is mentioned in 1495.

In the 14th century it is likely that the aljama of Toledo had in the district of Alacava two units each comprising a synagogue and a Rabbinic school or midrash, one situated on the old wall-walks of the Golondrinos and the other in the Bisbís-Caños del oro block.

The district could be defended from attacks from the exterior thanks to being provided with gates or wicket gates in the area of the Christian district of San Román and wicket gate which at one time was called Pepino, further to the west. The existence of these gates posits the theory that this district was closed on its northern side by a wall. The fact that neither this wall nor the gate at the level of the church of San Román are mentioned after the 12th century perhaps can be put down to its probable destruction by the troops of Enrique II in 1355 or by the revolts of 1391. To the south, in contact with Ángel street, the transversal streets of Alacava were closed off by gates which, in turn, were protected by lean-tos.

For a better understanding of this paved complex, we need to imagine a Jewish quarter compartmentalised into different walls or wall-walks erected in accordance with the progressive expansion of the Jewish population, not totally closing off the block but setting specific limits between Jewish and Christian territories. What´s more, until 1480, in other words, virtually throughout their history, the Jews of Toledo were not in actual fact forced to reside in the interior of the Jewish quarter, maintaining businesses and homes in different parts of the city.

Glossary

- jewish quarter: Traditional name given to the Jewish district or part of a city where the Jews´ homes were concentrated. In some cases it was determined by law as an exclusive place of residence of the members of this community. By extension, the term applies to any area known to be inhabited by families of Jewish culture.

- mikveh, l. heb: Ritual bathing. Space where the purification baths prescribed by Judaism are taken.

- mudejar: Moslems who continued living in the territory reconquered by the Christians. They were allowed to keep practising the Islamic religion, use their language and maintain their customs.

- sephardi, l. heb: Jew of Hispanic origin.

- sofer, l. heb: Jewish Scribe who has the task of transcribing the Torah and religious texts like the Tefillin and Mezuzah. The soferim are experts in Hebrew calligraphy and their work entails the observance of very precise writing rules both as regards the forms and formation of the lettering as well as in the instruments deployed.

- torah, l. heb: Text of the first five books of the Bible.

- wall-walk: Path around a city wall or parallel to it. In medieval Islamic cities it is the cul-de-sac which leads to private homes and which is closed at its entrance.

- aljama, l. heb: Specific institution of the Medieval Hispanic kingdoms which dealt with the governance and internal administration of the Jewish community.

- bailiff: A charter of the kingdoms of the former Crown of Aragón. The one was called the General Bailiff though there were Bailiff with jurisdictions in more specific areas. Its responsibilities include judging cases between Moslems and Jews.

- circle: Discs which appear as a decoration, frequently coloured, in chapters of Jewish origin.

- coffered ceiling: Wood or beams located on roofs between whose holes adornments were placed. Generally speaking, this name refers to any roof with wooden decoration.

- collection: self-governing Jewish organisation which brought together several aljamas for economic reasons the distribution, valuation and collection of taxes to be submitted to the king.

- comitatus, l. lat: Elite company formed by well-trained soldier who volunteered to make an incursion into enemy territory.

- converts converts: A christened Jew who has converted to Christianity.Jews converted to Christianity who returned to their place of origin after expulsion.

- genizah, l. heb: Deposit of sacred books which the synagogues had dedicated to storing the manuscripts which remained in disuse. This was not carried out to conserve them but rather to prevent any document containing the divine name from being treated in an undignified manner.

- governor: High dignitary who managed or too forward a military and civil legal venture by mandate, behest and under royal command.

- lobed: Formed by a succession of lobes, like waves, which protrude in the edge.

- maravedis: Tax in force between the 13th and 18th centuries in the kingdoms of Valencia and Majorca by James I under the statute of April 14th 1266 and it consisted of payment of seven royal sueldos of Valencia (one maravedi) every seven years for each dwelling which had property valued at fifteen maravedis or more.

- midrash, l. heb: Biblical text exegesis method aimed at study and reach which facilitates an understanding of the Torah. By extension, Rabbinic school.

- nasi, l. heb: Lit. Prince; by extension, a character of prestige.

- synagogue, l. gr: Gathering place for faithful Jews and the place of worship and studies. The term comes from the Greek synagogē which means place of congregation.